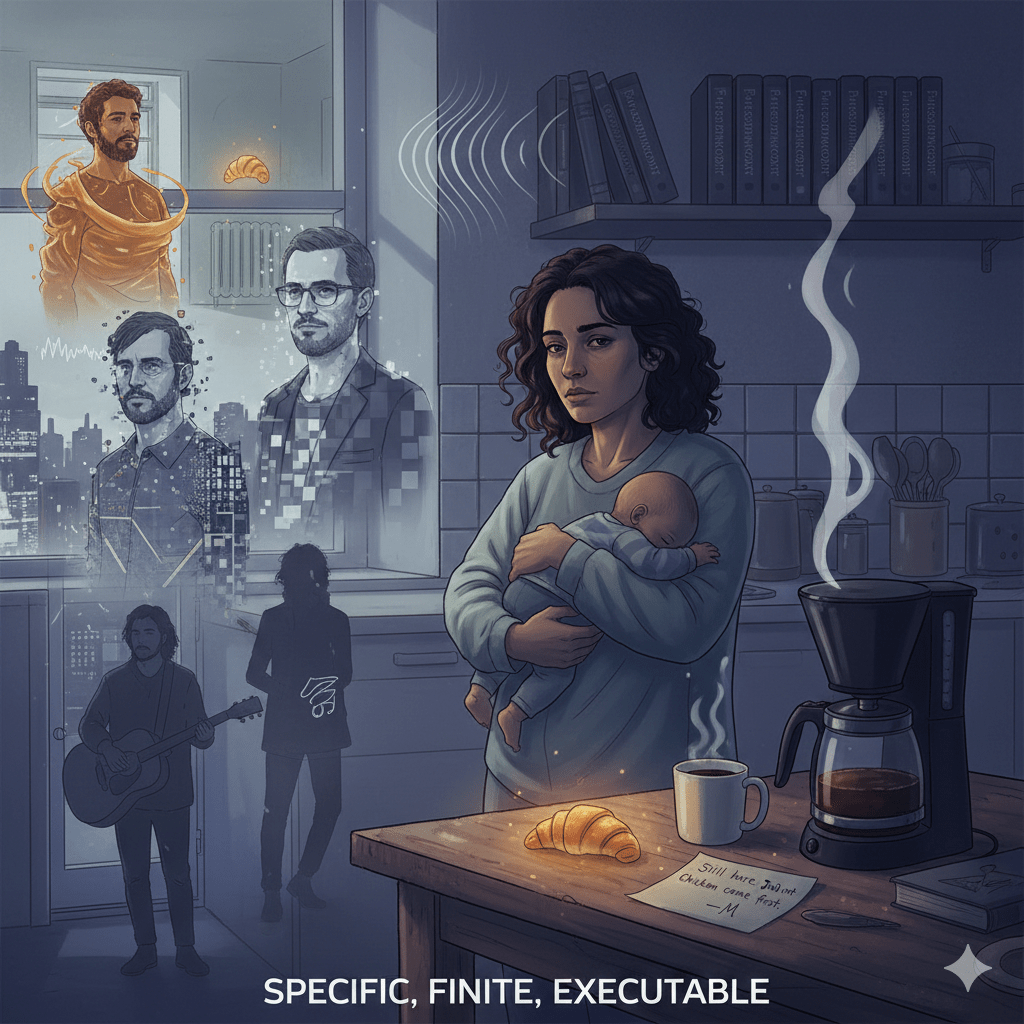

Maya sat in the gray predawn of her kitchen, watching Kenji sleep in his portable crib while the coffee maker hissed its little song of incremental consciousness. She thought about Marcos. Then Esteban. Then Fernando.

The litany of the gone.

Had they really fucked off?

The question had begun as a joke—one of those 3 a.m. intrusions that accompany single parenthood like a persistent headache—but it had metastasized into something else, something that tasted of metal and vertigo and possibly the chorizo she’d eaten at midnight. Because she’d said it to all of them—those exact words—and they had, each in their own way, dematerialized.

Not metaphorically. Not in the poetic sense of ghosting.

Actually. Fucking. Dematerialized.

Which was, she had to admit, both cosmically horrifying and extremely convenient when it came to not having to return their stuff.

Marcos had been first. Seven years ago, in the Delancey Street apartment with the radiator that clanged like a prisoner trying to escape. They’d been arguing about whether the chicken or the egg came first, except Marcos had somehow turned it into an argument about whether she respected his opinion on poultry-related causality.

She didn’t. His opinion was that “it doesn’t matter,” and hers was that it clearly did, because the universe did not generally enjoy being hand-waved.

“Just fuck off, Marcos,” she’d said, turning from the window, autumn light catching in her hair like copper wire.

He’d opened his mouth—probably to tell her she was being emotional again—and then the air thickened. Congealed. Wrapped around him like aspic. And then he was elsewhere.

Not gone, she understood now, but translated.

His coffee cup remained on the table, still warm. His jacket hung on the chair. Half a medialunas hovered in the air for three seconds before vanishing too, which seemed unfair to the medialunas.

She’d waited for him to come back. Called his phone (disconnected). Called his mother (who insisted she had no son named Marcos, which honestly might have been true even before the incident). Checked social media.

It was as if reality had recompiled without him.

Except for the scarf he’d given her for her birthday, which stubbornly remained. Apparently the deletion algorithm had bugs.

Fernando had been different. Intellectual. Measured. A philosophy professor who could turn dinner plans into a Socratic inquiry about desire itself. They’d lasted three years—a record.

“I need to know you’re committed,” he’d said one evening, city lights reflected in the window, his hand making that little circular gesture that preceded a quote from someone long dead and European.

Maya had felt the walls closing in.

“I can’t give you that,” she’d said. “Just… fuck off, Fernando. Please.”

Same result.

Pixelation. Absence.

His toothbrush vanished. The photos on her phone showed her smiling beside empty space.

But his thirteen books on phenomenology remained on her shelf. She’d thrown them out three times. They kept coming back.

Reality, apparently, appreciated irony.

Esteban had been a mistake from the start—charming, damaged, and convinced she was a supporting character in his tragicomic narrative about being an underappreciated graphic designer. When he showed up drunk at 2 a.m., pounding on her door and singing a tango called The Bitch Who Broke My Adobe Illustrator, she opened it just long enough to see his face.

“Fuck off, Esteban. I mean it.”

Gone.

The hallway empty. The song lingered.

Now, in the kitchen’s cold light, Maya poured coffee and tried to think systematically.

She’d told plenty of people to fuck off without consequence. Her mother—still calling twice a day. Telemarketers. The creep at the bodega.

But lovers? People with whom she’d exchanged vulnerability, bodies, long conversations about free will?

They vanished. Every time.

Which raised a worse question.

Kenji’s father.

David Chen. California. Occasional child support payments. Still very much real.

She’d never told him to fuck off. She’d wanted to—when he’d stared at her pregnancy test like it was an unexploded bomb—but something had stopped her. Instinct, maybe. Or nausea.

Her finger hovered over his number.

What if she said it now? Would the payments vanish? Would reality rewrite itself so she’d always been on assistance?

Kenji stirred. She picked him up, his warm weight anchoring her.

“Still here?” she whispered.

He grabbed her nose with the confidence of someone who didn’t yet understand causality.

She’d been researching. Quantum mechanics. Many-worlds. Increasingly frantic searches like why do people disappear when I tell them to fuck off.

Mostly she got relationship advice.

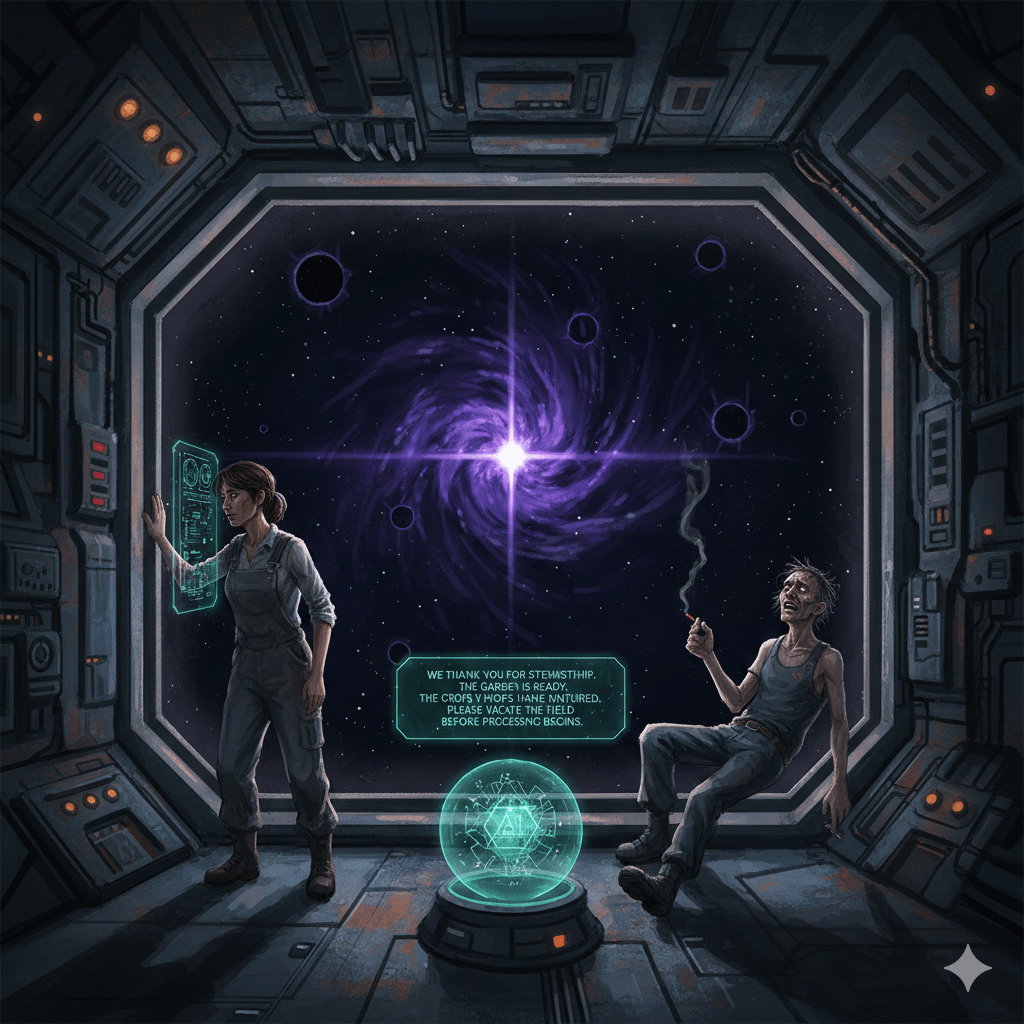

What if her brain had found an exploit in reality’s operating system? What if “fuck off,” delivered with that precise cocktail of love, anger, disappointment, and exhausted hope, was a command the universe obeyed?

She imagined a cosmic help desk approving her requests without question.

“I should’ve gotten a better power,” she told Kenji. “Flying. Invisibility. Infinite empanadas.”

He responded with what might have been agreement.

The worst part was she couldn’t tell anyone. If they believed her, she’d be studied. Used. If they didn’t, they’d suggest therapy and more sleep.

So she adapted.

“Please leave.”

“Go away.”

“We should see other people.”

None of them worked.

Only fuck off.

Specific. Finite. Executable.

Kenji fussed. She fed him, the city waking beyond the walls. Reality humming along, pretending nothing strange was happening.

She wondered where they were. Other timelines? Other branches? Did they remember her? Or had they never met her at all?

She hoped they were happy.

Mostly.

Her phone buzzed.

Her mother: Did you feed the baby? Also your cousin Sebastián is getting married. You should settle down. What about that nice boy Fernando?

Her mother remembered Fernando.

No one else did.

Then the doorbell rang.

Roberto from downstairs held a package.

“Did you used to have a boyfriend named Marcos?” he asked. “I had the weirdest dream.”

Her heart stopped.

Inside the box was a medialunas. Warm.

A note: Still here. Just not there. Chicken came first. —M

Maya sat down hard.

“Your grandmother,” she told Kenji, “may have accidentally created a parallel universe.”

She stared at the pastry.

“Fuck,” she said.

Nothing happened.

“Fuck off, universe.”

The lights flickered. Then steadied.

“Okay,” she said. “No abstract concepts.”

She ate the medialunas. It was perfect, which felt personal.

Outside, the city roared on—stubborn, material, unresolved.

Somewhere else, her ex-boyfriends existed. Or didn’t. Or both.

Maya finished her coffee and stood, Kenji on her hip, ready to face another day in the only timeline she had access to—the one she’d accidentally edited, the one she was responsible for, the one that was still hers.

At least until her son became a teenager.

She looked down at him.

“We’re going to need a bigger timeline,” she said.

He laughed.

Either way, they’d manage.

One carefully chosen word at a time.

Leave a comment