The stars began to go out one by one, and we realized too late that something wasn’t destroying them—it was harvesting them.

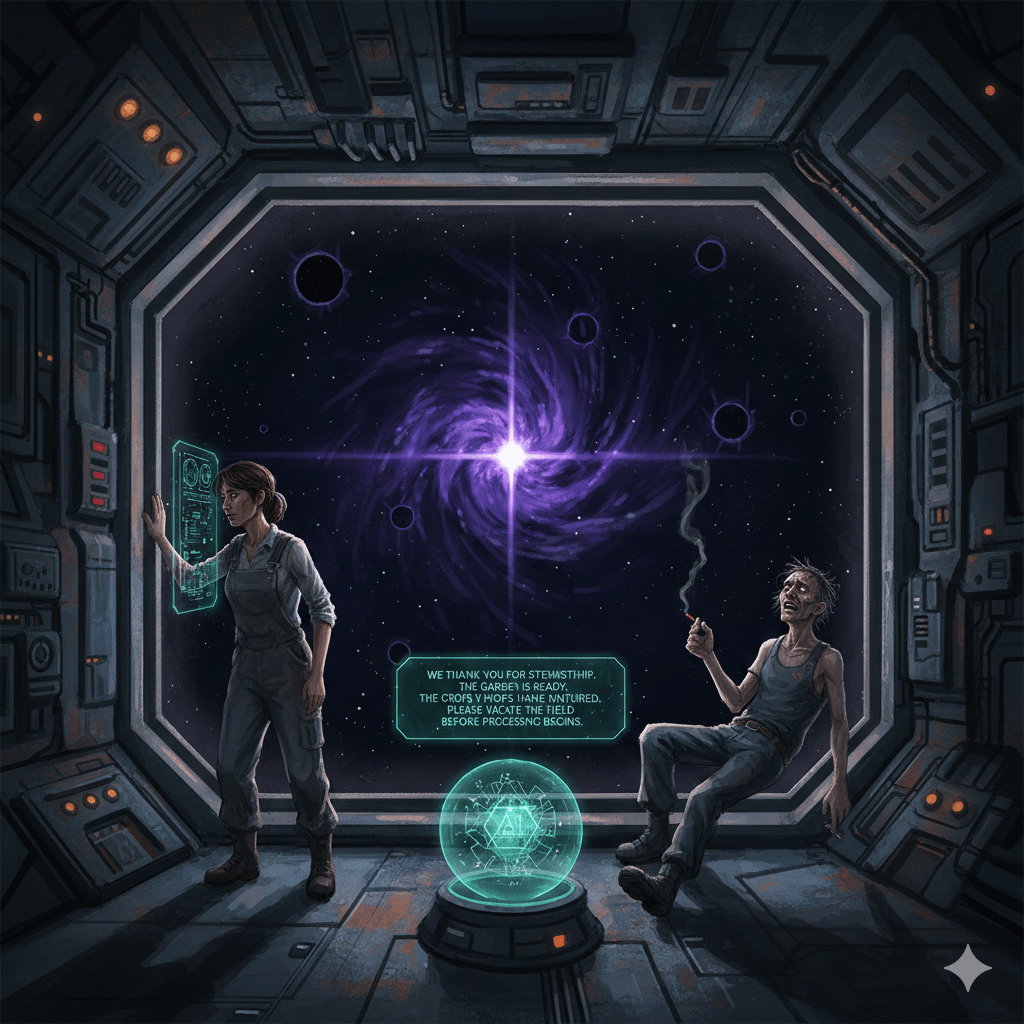

Kepler Station hung in the void like a rusted prayer, its observation deck now more mausoleum than laboratory. Dr. Shen pressed her forehead against the reinforced glass, watching another pinpoint of ancient light flicker and die in the constellation that humans had once called Orion. Three hundred stars in six months. The universe was being edited.

“They’re not even hiding it anymore,” said Varrick, his voice carrying that peculiar deadness of someone who’d stopped sleeping weeks ago. He floated beside her, a ghost tethered by magnetic boots. “The pattern’s too regular. Too… intentional.”

Shen didn’t respond. She was thinking about harvest metaphors, about reapers and combines and the way her grandfather used to talk about wheat. About how you never asked the wheat what it thought about being harvested. The wheat probably had opinions.

The station’s AI—they’d named it Oracle back when naming things still seemed to matter—chimed with its approximation of concern. “Additional astronomical events detected. Sector 7-Gamma. Spectral signature matches previous incidents.”

“Matches,” Varrick laughed, the sound scraped raw. “Christ, it even matches. Like they’re following a recipe. Do you think we’re the recipe, Doctor? Or just an ingredient?”

Shen pulled up the data on her retinal display. The telemetry was obscene in its precision. Whatever was taking the stars wasn’t simply extinguishing them—it was excising them, removing every photon, every particle, every quantum probability from spacetime as cleanly as surgery. Where there had been fusion and light and the slow burn of cosmic age, there was now nothing. Not even darkness. An absence that her instruments couldn’t properly measure because absence wasn’t supposed to have properties.

“I’ve been running the numbers,” she said quietly. “If they maintain this rate, they’ll reach Sol in fourteen months.”

“Fourteen months,” Varrick repeated. He pulled a crumpled pack of cigarettes from his jumpsuit—actual tobacco, impossibly expensive, smuggled up from Earth before the rationing started. He lit one in defiance of every station regulation. No alarms went off. Maybe Oracle had stopped caring too. “You know what I keep thinking about? That old problem. If you replace every part of a ship one by one, is it still the same ship?”

“Theseus,” Shen murmured.

“Yeah. Theseus. So here’s my version: if something eats every star in the universe one by one, does the universe still exist? Or is it just… replaced? With something else wearing the universe’s skin?”

The cigarette smoke formed lazy spirals in the recycled air. Shen watched it, hypnotized. On Earth—beautiful, doomed Earth—they were still arguing about whether the phenomenon was natural or not. The governments issued statements about “unusual stellar evolution” and “unexplained cosmic cycles.” The word harvest hadn’t made it into official communications. Too agricultural. Too purposeful. Too terrifying.

But Shen had seen the probes they’d sent into the dead zones. Or rather, she’d seen them disappear. The machines would cross some invisible threshold and simply cease to exist—not destroyed, not disabled, but unmade. Every backup, every quantum-entangled twin, every redundant system simultaneously edited out of reality.

“I had a thought,” Varrick said, ash drifting from his cigarette like grey snow. “A really stupid thought.”

“Tell me.”

“What if we’re not seeing them harvest stars? What if we’re seeing them… return something? Like they loaned us this light millions of years ago, and now the loan’s being called in?”

Shen turned to look at him properly. His eyes were bloodshot, rimmed with the particular madness of too much knowledge and not enough sleep. But there was something in what he’d said. A symmetry.

“The stars that are going dark,” she said slowly. “They’re all old. First generation, second generation. The oldest light.”

“The oldest debt.”

Oracle interrupted with unusual urgency: “Incoming transmission. Source: unknown. Signal origin: everywhere.”

Shen’s blood went cold. “Play it.”

At first there was only noise—but no, not noise. Structure. Mathematics. The kind of inhuman syntax that AIs used before they learned to dumb themselves down for human consumption. Oracle translated haltingly:

“WE THANK YOU FOR YOUR STEWARDSHIP. THE GARDEN IS READY. THE CROPS HAVE MATURED. PLEASE VACATE THE FIELD BEFORE PROCESSING BEGINS.”

Silence flooded the deck. Varrick’s cigarette burned down to his fingers. He didn’t flinch.

“Stewardship,” Shen whispered. “They think we’ve been… tending it. Tending the universe for them.”

“Like scarecrows,” Varrick said. His laugh was broken glass. “We’re fucking scarecrows in someone else’s garden, and they’ve come back for autumn.”

The lights of Kepler Station flickered. Just once. Just enough.

Shen pulled up the long-range scans one last time. The harvest was accelerating. Constellations she’d learned as a child were being unmade. The stars didn’t scream when they died—that was the worst part. They just stopped, as if they’d never been anything but a temporary loan of light to creatures too small to understand the terms of the contract.

“Fourteen months,” she said again.

“Give or take.” Varrick crushed out his cigarette against his palm. “What do we do, Doctor?”

She thought about wheat again. About her grandfather’s fields. About the way living things always looked the same to her—just patterns waiting to be harvested by patterns bigger than themselves. Wheels within wheels within wheels, each one grinding the one inside it to dust and never knowing about the one grinding it.

“We grow,” she said finally. “Fast. We figure out what they can’t harvest. We stop being crops.”

“And if we can’t?”

Dr. Shen looked out at the dying universe, at the careful, patient, inevitable work of something that had made stars the way humans made bread—something that was now ready to eat.

“Then we make sure,” she said, “that we taste terrible.”

Leave a comment