Part One: The Invitation That Wasn’t

Kate Hopstead had been crouching in Yellowstone snow for six hours when her camera disappeared. Not stolen—disappeared. One moment the Nikon hung against her chest, frost-rimmed and faithful, the next moment her sternum pressed against the cold absence where it should have been.

The wolf she’d been tracking—a scarred alpha with eyes like brass coins—sat twenty meters away, watching her with what she would later swear was amusement.

“You’re not real,” she told the wolf. Perhaps she was telling herself. Or maybe she spoke to the space between them that seemed to shimmer like August asphalt.

The wolf yawned. Inside its mouth, instead of teeth and tongue, she saw stars.

That was the moment Kate realized everything she’d photographed for twenty years had been practice. She captured every Canis lupus in every wilderness on every continent. Audition. Resume for a job she hadn’t known she was applying for.

The scarred alpha spoke without moving its jaws: “We’ve been watching your portfolio.”

Part Two: Spacefold Taxonomy

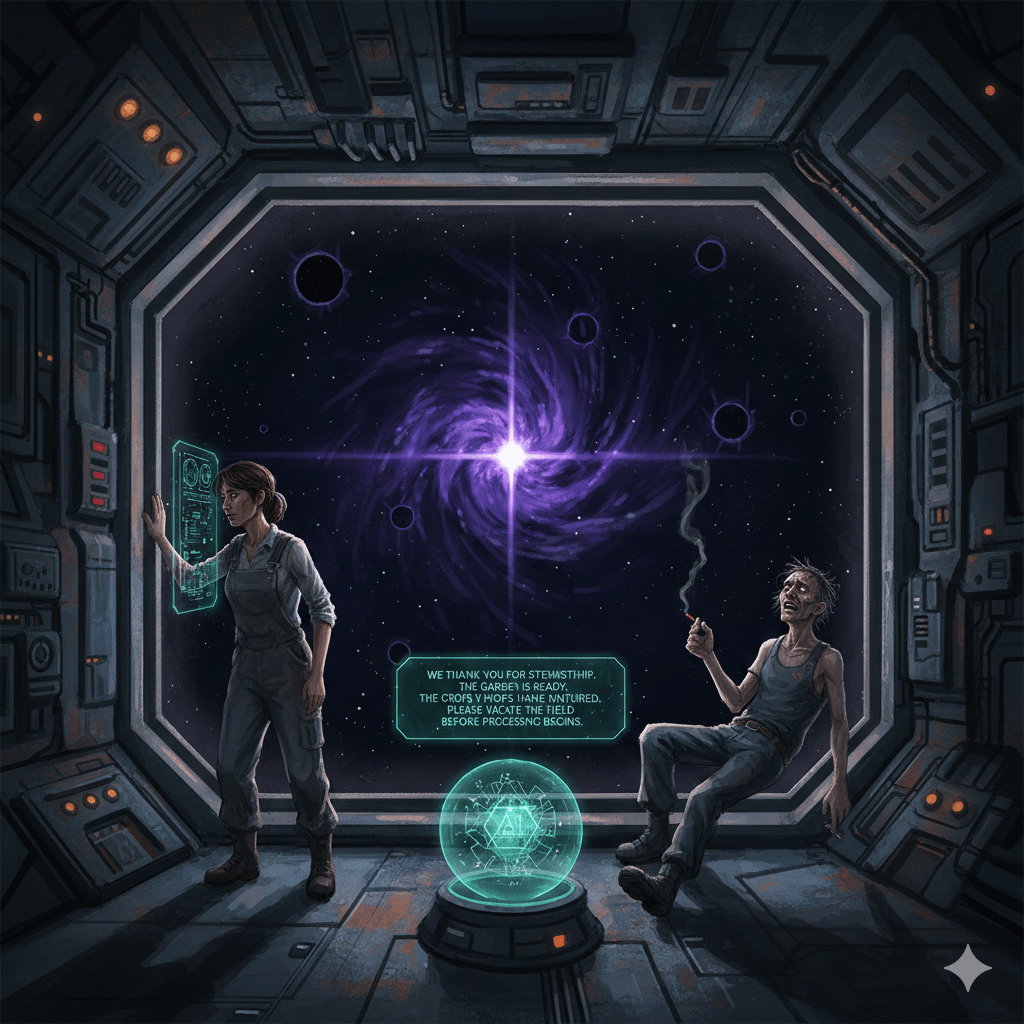

The ship didn’t look like a ship. It looked like memory, like the sensation of almost-remembering something important. Kate found herself inside it without boarding. She stood in what might have been a cargo hold. It might have been a cathedral. It might have been both at the same time. That was very much the point.

“You’ll be documenting the Lycaon Dispersal,” said the being. It was either her employer, her kidnapper, or possibly her delusion. It wore a human shape the way children wear cardboard boxes pretending to be robots—approximately, enthusiastically, unconvincingly.

“The what?”

“Throughout the galaxy, wherever certain conditions emerge—similar atmospheric pressure, similar prey density, similar moonlight—wolf-shaped things evolve. Independent. Parallel. Inevitable, like crystals growing in solution.” The being flickered. “We need them documented before the Confluence.”

“What’s the Confluence?”

“The moment when they realize they’re all the same thing. Or were always the same thing. Or will become the same thing. Temporal linguistics makes this difficult.” The being reformed into something briefly resembling an insurance adjuster. “You have six local months. Your camera is everywhere you look. Your compensation is returning home with your mind mostly intact.”

Kate thought about her apartment in Missoula. She also thought about her ex-husband who’d left because she loved wolves more than predictability. Lastly, she considered the scarred alpha with stars in its mouth.

“Mostly intact?”

“Guarantees are expensive.”

Part Three: The Lupine Cartography

Planet Seven (Designation: Yelp-When-Wounded):

The wolves here had crystalline fur that sang in the wind, individual notes for individual hairs. They hunted in harmonics. Kate’s camera recorded the sound as light, light as sound. She forgot which was which. When she checked her notes later, she’d written: “Remember: red is the sound of hunger, blue tastes like distance.”

Planet Nineteen (Designation: The-Place-Where-Running-Is-Prayer):

These wolves were made of smoke and obligation. They existed only when observed, and only believed in themselves collectively. Kate had to photograph the entire pack simultaneously or capture nothing. She spent three weeks building a rig of ninety-seven cameras triggered by a single breath. The resulting image showed her own reflection multiplied into a pack, each version with different colored eyes.

She deleted it immediately.

She did not delete it. It deleted itself. It’s still deleting itself, recursively, forever.

Planet Forty-One (Designation: Grief-Simplified):

No wolves here. Only the space wolves should occupy. The prey animals moved in patterns accounting for predators that didn’t exist, evolutionary trauma encoded in their nervous systems. Kate photographed the absence. Later, viewing the images, she saw wolf-shaped holes in reality, predator-shadows cast by no source.

Her employer/kidnapper/delusion appeared beside her. “These are the most important,” it said. “Document what should be but isn’t. The universe keeps receipts.”

Part Four: The Convergence Interview

By planet seventy-three, Kate had stopped sleeping. Not couldn’t sleep—stopped. Sleep seemed to her an affectation, like wearing a hat indoors. The wolves of Designation: Speaking-In-Prophets told her stories about the heat-death of meaning. The wolves of Designation: Twice-Removed-From-Tuesday showed her her photographs. They demonstrated how they would appear to beings who experienced time as a spatial dimension.

“I don’t understand what I’m documenting anymore,” she told her camera. It had become indistinguishable from her hands. Her camera had become indistinguishable from her seeing.

The scarred alpha from Yellowstone appeared. Maybe it had always been there. It could eventually be there, depending on which frame of reference you privileged.

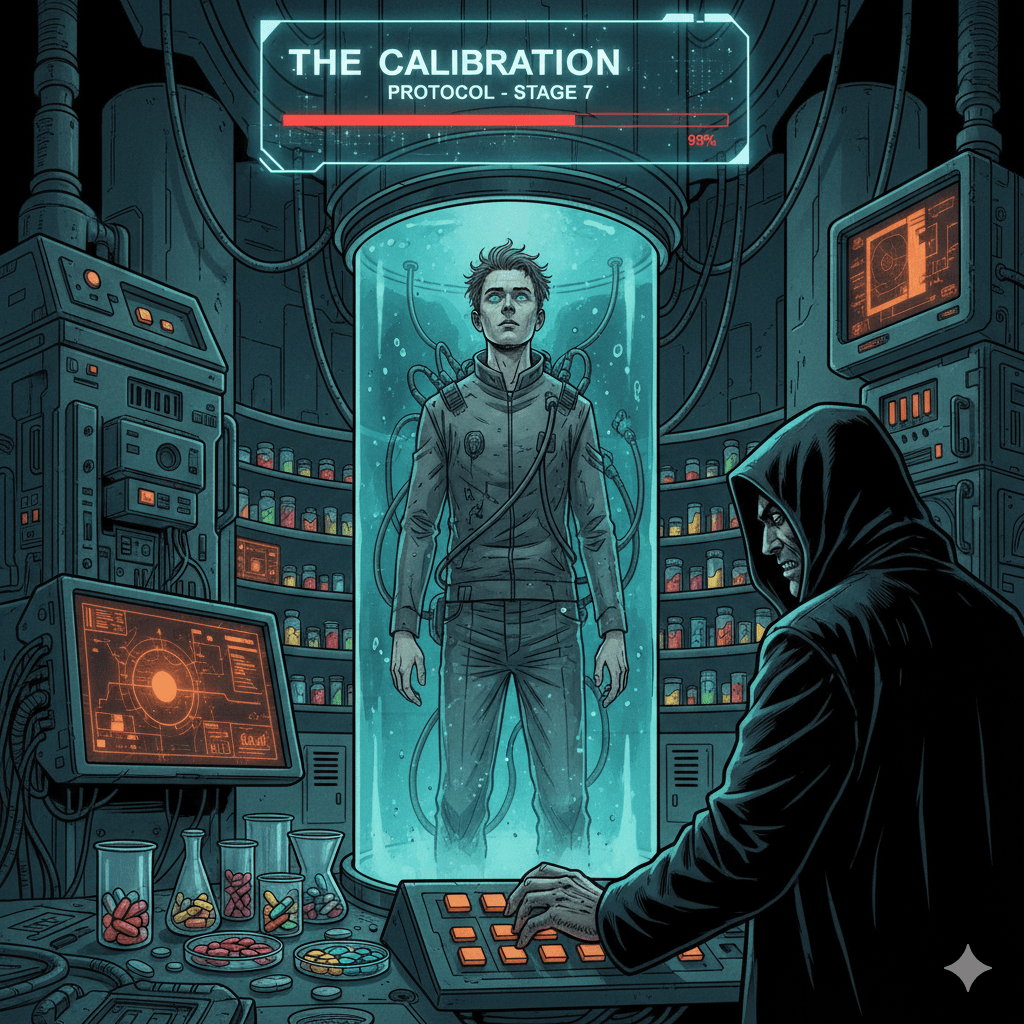

“You’re documenting the moment before awakening,” it said. “All these wolves, across all these worlds—they’re about to remember they’re one thing. One vast, distributed organism thinking itself into existence across galaxies. Your photographs are the last record of their individuation. Their childhood.”

“Why me?”

“Because you knew how to look at wolves and see both the wolf and the act of wolfing. Both the thing and the verb of the thing.” The alpha sat, which was also lying down, which was also running at full speed. “Most documentarians see only nouns. You’ve always understood that wolves are conditional statements.”

Part Five: The Return That Was Always Happening

Kate came back to Yellowstone. However, she remained simultaneously on seventy-three other worlds. This was apparently fine. This was apparently how it worked now. The Confluence happened or was always happening or would keep happening. Her photographs existed in museum-galleries. They spiraled through dimensions. In these places, “museum” and “gallery” meant something closer to “communal dream” or “mandatory vision.”

She found her old apartment in Missoula. Inside, there were ninety-seven versions of her morning routine, all happening at once, all slightly different. In one version she made coffee. In another, coffee was a form of prayer. In a third, prayer and coffee had merged into a single sacrament.

Her ex-husband called. “I saw your work,” he said. “I don’t understand it.”

“Neither do I.”

“Are you okay?”

Kate looked out her window at the street. Wolves made of probability and intention walked among the pedestrians. Most couldn’t see them. Some could see them but had no language for seeing them. Others had always seen them but pretended otherwise out of politeness.

“I’m mostly intact,” she said.

After she hung up, she downloaded her photographs onto her computer. This computer was every computer. It was the idea of computation rendered in lupine form. The images arranged themselves into patterns. These patterns predicted the future, or remembered the future. They created the future through the act of anticipation.

The scarred alpha appeared one last time. She sat in her living room. It was the space where her living room used to be. She understood that rooms were just agreements about where walls should go.

“Final question,” Kate said. “Were the wolves real?”

“Define real.”

“I can’t.”

“Then there’s your answer.” The alpha stood to leave. “You’ve documented the moment when the galaxy learned to hunt itself. When distributed intelligence achieved lupine consciousness. When—”

“Stop,” Kate said. “Just tell me one true thing.”

The alpha considered this. “Wolves,” it said finally, “are what the universe looks like when it wants to be witnessed. You spent your life witnessing. Now the universe is witnessing back.”

Then the alpha was gone, or had never been there, or would arrive shortly depending on which observer you asked.

Kate picked up her camera. It was also her eyes. It was also her purpose. It was also the question she’d been asking since Yellowstone without knowing she was asking it.

Outside, the wolves that were everywhere and nowhere waited to be photographed. They waited to be seen. They longed to be verbed into existence by someone who understood that observation and creation were the same gesture. These acts are performed with different emphasis.

She stepped outside to document them.

She was already documenting them.

She would always be documenting them.

The shutter clicked like a heartbeat. It was like a prayer. It sounded like the universe saying yes to its own becoming.

Somewhere, on seventy-three worlds, Kate Hopstead was still crouching in the snow. She was waiting for the perfect shot. The wolves, who were her subject, her audience, and herself, watched with eyes like brass coins. They looked like binary stars and like the answer to a question photography was just learning how to ask.

Leave a comment