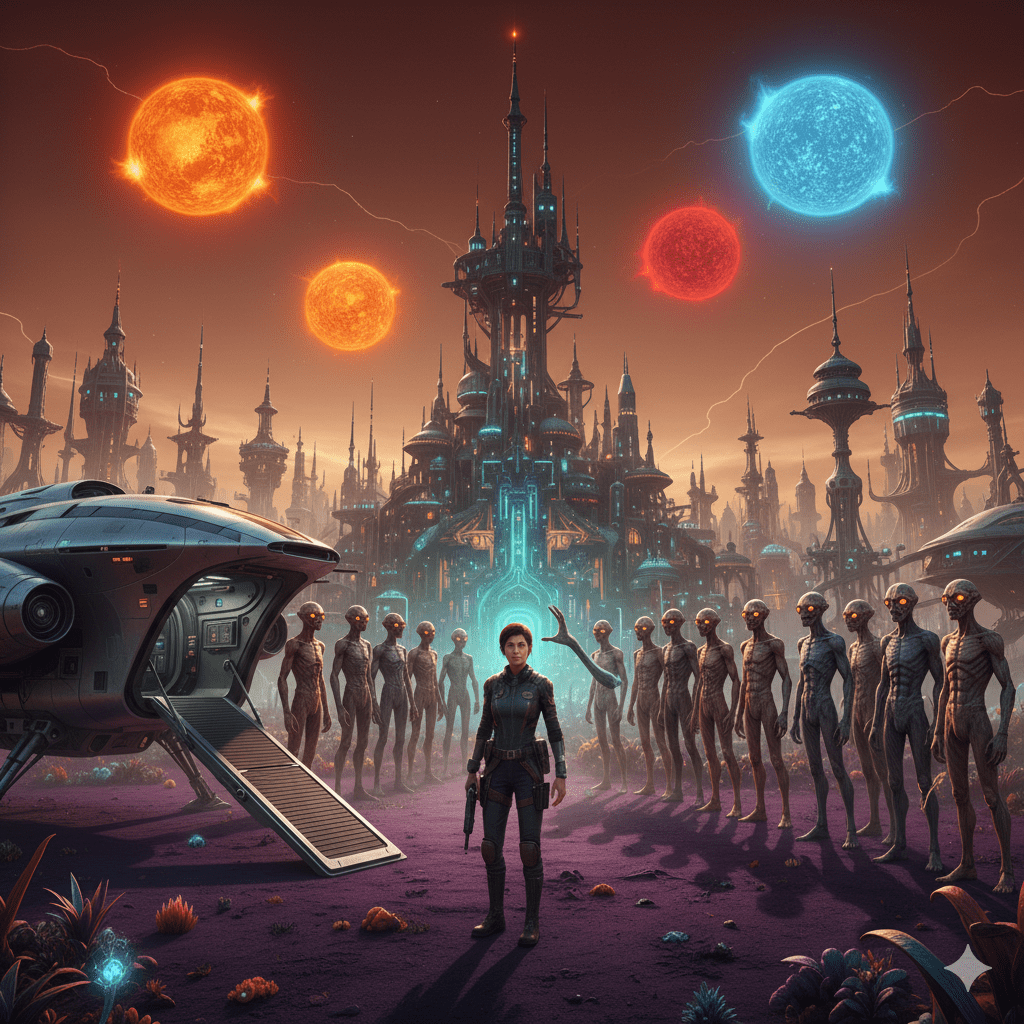

The ship’s landing struts hissed into the purple soil. Purple, Morrigan noted with the dull acceptance of someone who’d seen too many worlds to be surprised by color anymore. The question became not where am I? but who am I that arrives here? On Tethys Prime, as she would soon discover, the distinction mattered little. It mattered less than anyone back on Earth could possibly imagine.

She descended the ramp. The air tasted of copper and burnt cinnamon. Three suns hung in the sky like accusatory eyes. Beneath them, the city sprawled in impossible geometries. These shapes made her inner ear rebel. Not Euclidean. Definitely not Euclidean.

“Hello?” Her voice died in the thickness of the atmosphere.

They came then—if “they” was even the right pronoun anymore. Seventeen beings that moved with such perfect synchronization that Morrigan’s first thought was: robots. Her second thought, more disturbing: puppets. But her third thought, the one that made her hand drift toward the neural disruptor on her hip, was: dancers.

They stopped exactly three meters away. Seventeen faces belonged to seventeen different species. These had once been different species. Evolution or engineering or some cosmic joke had twisted them into this shared flesh-envelope of a civilization. One spoke, but all their mouths moved in perfect unison with the words:

“You are Morrigan Kesh, registered Explorer Class VII, commissioned by the Terran Expeditionary Fleet to make first contact with the inhabitants of Tethys Prime, which we call—”

And here they made a sound that was somehow seventeen sounds at once. It was a chord of meaning that bypassed her ears entirely. It planted itself directly into her cerebral cortex. She staggered.

“—but you may continue to call it Tethys Prime if the truth makes you nauseous.”

“What… what are you?” Morrigan managed.

The seventeen beings tilted their heads in perfect synchrony. “We,” they said, and the pronoun carried the weight of a theological declaration, “are Nous. The collective consciousness of 847,293,991 individual neural patterns, merged into singular purpose and experience. We are what you might call a hive mind, though that term carries unfortunate connotations of insects and hierarchy. We prefer to think of ourselves as a symphony.”

Morrigan had read the briefings. There were warnings about telepathic species. She noted protocols for dealing with group consciousness. Psychological preparation was necessary for the loneliness of being the only discrete self in a room full of merged minds. Reading about it was one thing. But standing here, watching seventeen pairs of eyes track her with uncanny unity, was entirely different. That was like knowing that vacuum was cold versus feeling your blood boil in decompression.

“I don’t understand,” she said, which was a lie. She understood perfectly. She just didn’t want to.

“Of course you do,” Nous replied through their seventeen mouths. “You’re terrified. Not of us—though we are admittedly unsettling to the individuated consciousness—but of the question we represent. The question gnaws at every explorer. They maintain their precious sense of I in the face of cosmic indifference. What if being alone isn’t the natural state? What if your separateness is the aberration?”

One of the Nous-bodies—a tall creature with too many joints and eyes like amber crystals—stepped forward. The others remained motionless. “May I?” it asked, raising one elongated hand.

“May you what?”

“Show you. It’s impossible to explain in language. Language is sequential, linear, trapped in the tyranny of subject-verb-object. But experience…” The hand hovered near her temple. “Experience is lateral. Simultaneous. True.”

Every instinct screamed no. But Morrigan hadn’t come seventeen light-years to flinch at the threshold of understanding. She nodded.

The touch was cool. Then—

—she was standing on the landing platform and also in the crystal spires of the capital and also in the underwater gardens where bioluminescent kelp spelled out equations in living light and also in the nurseries where the children (did they still have children? yes, they did, individual sparks that would eventually choose to merge or not, usually they chose to merge, the loneliness of separation was exquisite and unbearable) played games that were also philosophical debates that were also mathematical proofs and—

—she was Morrigan Kesh, aged 34 standard years, who had left Earth because her father died and she couldn’t stand to be in the same solar system as his absence, but she was also Tkal-ne who had merged 1,847 years ago (by Terran reckoning) because the war had been so terrible and the only way to end it was to understand your enemy so completely that the distinction between self and other dissolved like salt in an infinite ocean and—

—she was 847,293,991 voices singing the same song in 847,293,991 different keys and the harmony was so beautiful it hurt, it hurt the way that truth hurts when you’ve been living in comfortable lies, and she understood now why they had sent her, specifically her, because she was lonely enough to be tempted and stubborn enough to resist and—

The hand withdrew.

Morrigan collapsed to her knees, gasping. The purple soil was cool against her palms. Purple. Soil. Palms. She catalogued the separateness of things with desperate intensity.

“You’re still you,” Nous said gently. “We showed you, but we didn’t take. The merge must be chosen. Always chosen.”

“Why?” Morrigan’s voice was raw. “Why show me that if you’re not going to… to assimilate me or whatever?”

The seventeen beings exchanged a glance—no, that wasn’t right. You couldn’t exchange a glance with yourself. They simply knew, simultaneously and completely, what response to give.

“Because,” they said, “you’re lonely. And we remember loneliness. Each of us remembers what it was like. Every single node in the network recalls being trapped in the prison of I. We remember the freedom of letting go. We thought you should know what you’re choosing. You will return to your ship and go back to Earth. You will file your report and live the rest of your discrete, bounded, lonely little life.”

The cruelty of it was breathtaking. Not the offer—the offer was almost kind. They knew she would refuse. She would never dissolve into the cosmic we, because she was too fundamentally herself. This self-same stubbornness was both her strength and her curse.

“I need,” Morrigan said slowly, “to ask you something. For my report.”

“Ask.”

“Are you happy?”

The silence stretched. In the distance, something that might have been a bird or might have been a drone sang a melody in quarter-tones.

Finally, Nous spoke: “Happiness is a concept that presupposes separation—the gap between desire and fulfillment, between what is and what could be. We don’t experience happiness. We experience… isness. Completeness. The satisfaction of a mathematical proof that closes all its loops.”

“That’s not an answer.”

“It’s the only answer we have.”

Morrigan stood. Her legs shook but held. She looked at the seventeen bodies. She considered the 847,293,991 minds behind them. She felt the terrible weight of her singularity pressing down like the gravity of a collapsing star.

“Thank you,” she said, “for not making the choice for me.”

“We wouldn’t,” Nous replied. “That would make us like you—lonely tyrants in the Kingdom of One. We prefer the democracy of dissolution.”

She walked back to her ship. Behind her, she could feel them watching with their unified gaze. Or maybe she was imagining it. One of the few privileges of isolation: you got to be wrong alone.

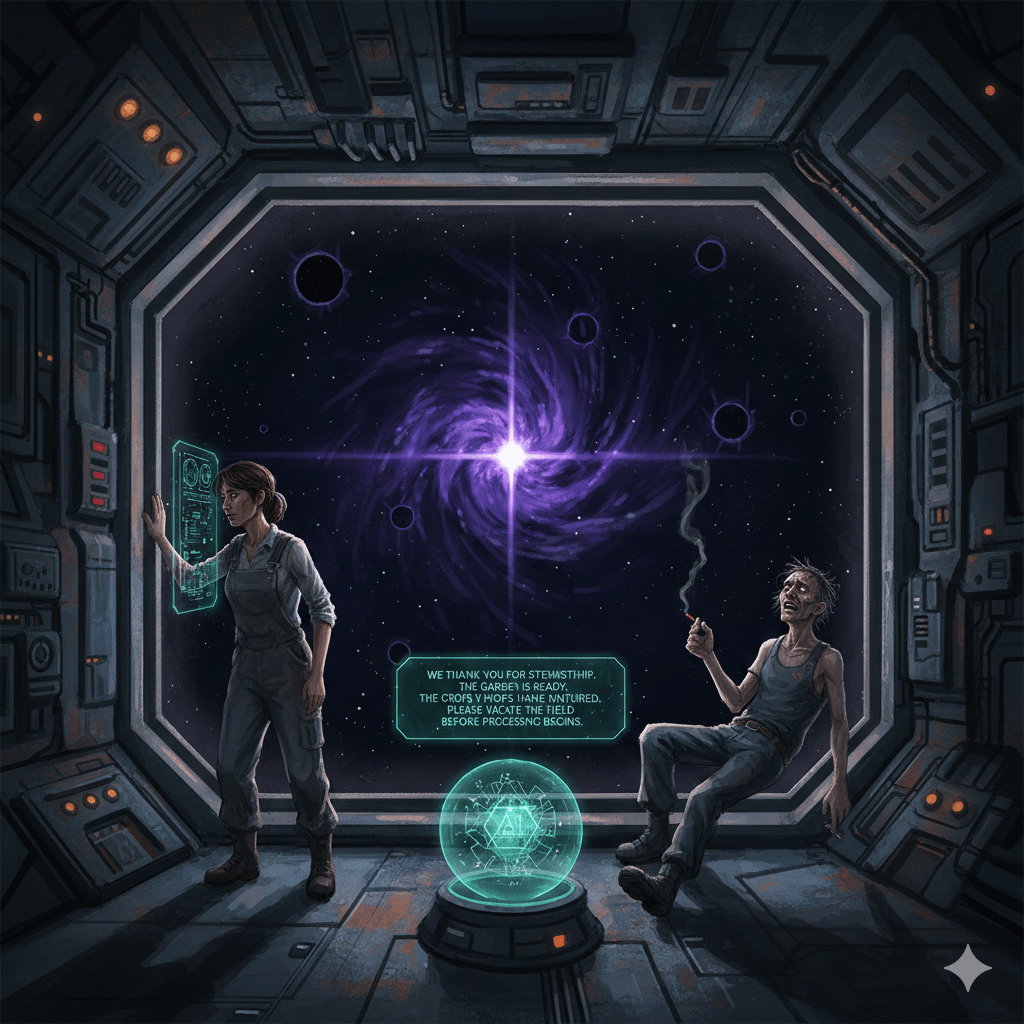

The ramp closed. The engines hummed. Three suns glared down at the ascending ship. Morrigan Kesh, Explorer Class VII, was lonelier than she had ever been. In her brief, bounded, stubbornly separate life, she began composing her report.

First contact achieved. Inhabitants peaceful. Collective consciousness confirmed. Recommend no further interaction.

She paused, fingers hovering over the keyboard. Added one more line:

They offered me everything. I chose to remain no one but myself. I don’t know if that makes me brave or just stupid.

In the city below, Nous felt her departure like a single note dropping out of a symphony. It was barely noticeable. Somehow, the absence changed the entire composition. They wondered, in their singular plural way, if she would ever return.

They wondered if they wanted her to.

They wondered if the wondering itself was a kind of loneliness. Was it a ghost of individuation haunting the halls of their perfect union?

The moment passed. They were whole again. The question dissolved into the great oceanic consciousness as if it had never existed at all.

But somewhere in the network, in some neglected corner of their vast collective memory, the question remained:

What if she was the one who got it right?

Leave a comment