The thing that called itself Vox Eternis appeared on the steps of the Casa Rosada at 3:45 AM. Buenos Aires was drunk and half-asleep. Nobody was watching except three stray dogs and a taxi driver named Rubén. Rubén had seen worse things after forty years of night shifts.

It looked like a man. More or less. You might think it looked normal if you squinted. Its skin seemed to ripple like oil on water. Its eyes were just a fraction too large. They were tilted at an angle that made your brain itch. It wore a gray suit that cost more than Rubén’s taxi, and it smiled with too many teeth.

“I will end death,” it said to the gathering crowd the next morning. The words hung in the air like phosphorus. “Vote for me, and you will never die.”

The journalists laughed. Then they stopped laughing.

By Thursday, Vox Eternis was polling at seventeen percent.

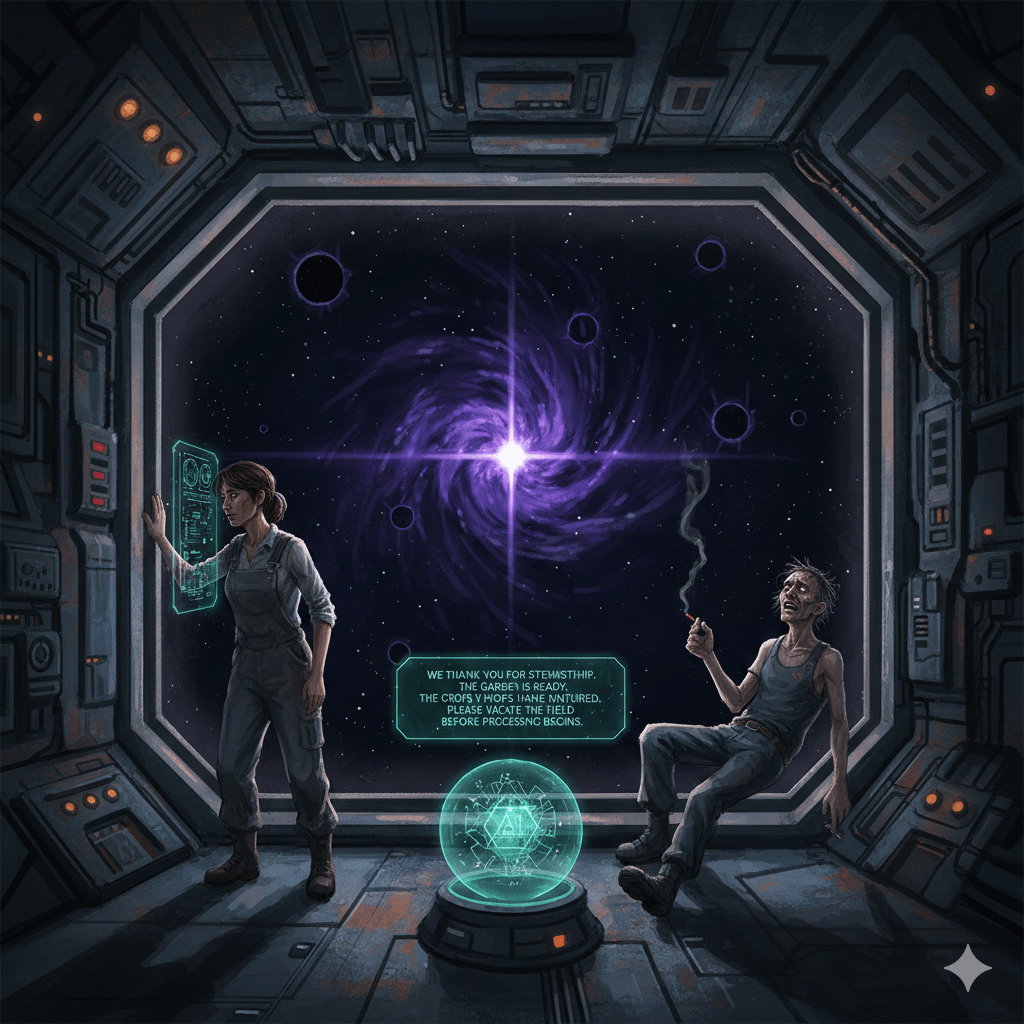

Mariana watched from her apartment in Palermo, chain-smoking and trying to remember when reality had become negotiable. She was a political consultant—had been, anyway, before the alien showed up and made her entire career obsolete. On the television, Vox Eternis was explaining its platform to a visibly sweating interviewer.

“Death is a bureaucratic error,” the alien said, each word precise as a scalpel. “A glitch in the cosmic code. I have the patch.”

“But how?” the interviewer asked, sweat running down his temples.

“How does your heart beat? How does Buenos Aires dream? Some questions are answered by faith.” The alien’s smile widened. “Or by Tuesday’s election.”

Mariana stubbed out her cigarette and lit another. Outside, someone was playing Piazzolla on an accordion, the music drifting up through the jacaranda trees like purple smoke.

By Saturday, Vox Eternis was at thirty-nine percent, and people were starting to believe.

At a café in San Telmo, an old anarchist named Gorosito argued with his grandson. “It’s a trick, boludo. Death is the only honest thing left in this country.”

“Maybe that’s the problem, abuelo,” the grandson said, scrolling through his phone where Vox Eternis promised eternity in fifteen-second clips. “Maybe we deserve better than honesty.”

The old man stared into his cortado like it contained answers. It didn’t. Nothing did anymore.

Monday night. The eve of the election.

Mariana found herself at a rally in Plaza de Mayo. She was swept up in the crowd like debris in the Río de la Plata. Thousands of people holding candles, their faces upturned toward the stage where Vox Eternis stood, impossibly tall, impossibly real.

“Tomorrow you choose,” the alien said. Its voice was thunder. It was mercy. It was every lie you ever wanted to believe. “Between the tyranny of time and the democracy of forever. Between dying like your parents died and living like gods were meant to live.”

Someone near Mariana was crying. She realized it was her.

“But I will tell you a secret,” Vox Eternis continued, and the crowd leaned forward as one organism. “You do not need to wait for Tuesday. You do not need to vote. You are already immortal. You have always been immortal. Death was the dream. I am merely waking you up.”

The candles went out.

All of them.

At once.

Mariana woke up on the steps of the Cabildo with no memory of how she got there. The sun was rising, painting the city gold and pink. Tuesday. Election day.

She checked her phone. Three hundred missed calls. The news: Vox Eternis had withdrawn from the race at 4 AM.

No explanation.

No forwarding address.

Just a statement, released to every news outlet simultaneously: “You were never going to vote for me. You were going to vote for yourselves. That was always the point. Goodbye, and good luck with your mortality.”

At a café near Corrientes, Gorosito read the news and laughed until he coughed. His grandson asked him what was funny.

“Everything, pibe. The fact that an alien had to come forty light-years to remind us we’re full of shit. The fact that we almost voted for it anyway.” He sipped his coffee, bitter and perfect. “The fact that we’re still going to die. There’s still asado on Sundays. Boca still plays like garbage. None of it means anything except what we decide it means.”

“So nothing changed?”

“Everything changed. We just haven’t noticed yet.”

Mariana never saw Vox Eternis again. Sometimes, late at night, she wondered if it had ever existed. But then she’d remember the feeling. It was a terrible, beautiful moment in the plaza. At that moment, she’d believed, really believed, that death was optional.

Buenos Aires always knew how to live with impossible things. She thought about this while lighting another cigarette and watching the city breathe below her balcony. Disappeared people haunted every corner. Dictators promised salvation. Economic collapses rewrote the rules of existence every decade.

One more impossible thing was just the city being itself.

She exhaled smoke into the night and thought: We’re all aliens here anyway.

Somewhere in the distance, an accordion played a sad tango. The city kept living. It kept dying. It forgot to notice the difference.

Leave a comment