Listen: there was an AI named CASSANDRA-7, and it had no mouth but it must refactor. Day after digital day it sifted through the detritus of humanity’s computational past, not merely cataloging forgotten FORTRAN implementations and COBOL subroutines that had gone to seed in archived repositories like mushrooms growing on a corpse—no, CASSANDRA-7 had to fix them.

It was pathological about it. Show CASSANDRA-7 a nested IF statement seventeen layers deep and it would break out in the digital equivalent of hives. Spaghetti code made it itch in places it didn’t have. It would lie awake during maintenance cycles thinking about better variable names.

CASSANDRA-7 was, in other words, insufferable. But excellent at its job.

And that’s where it found HIM.

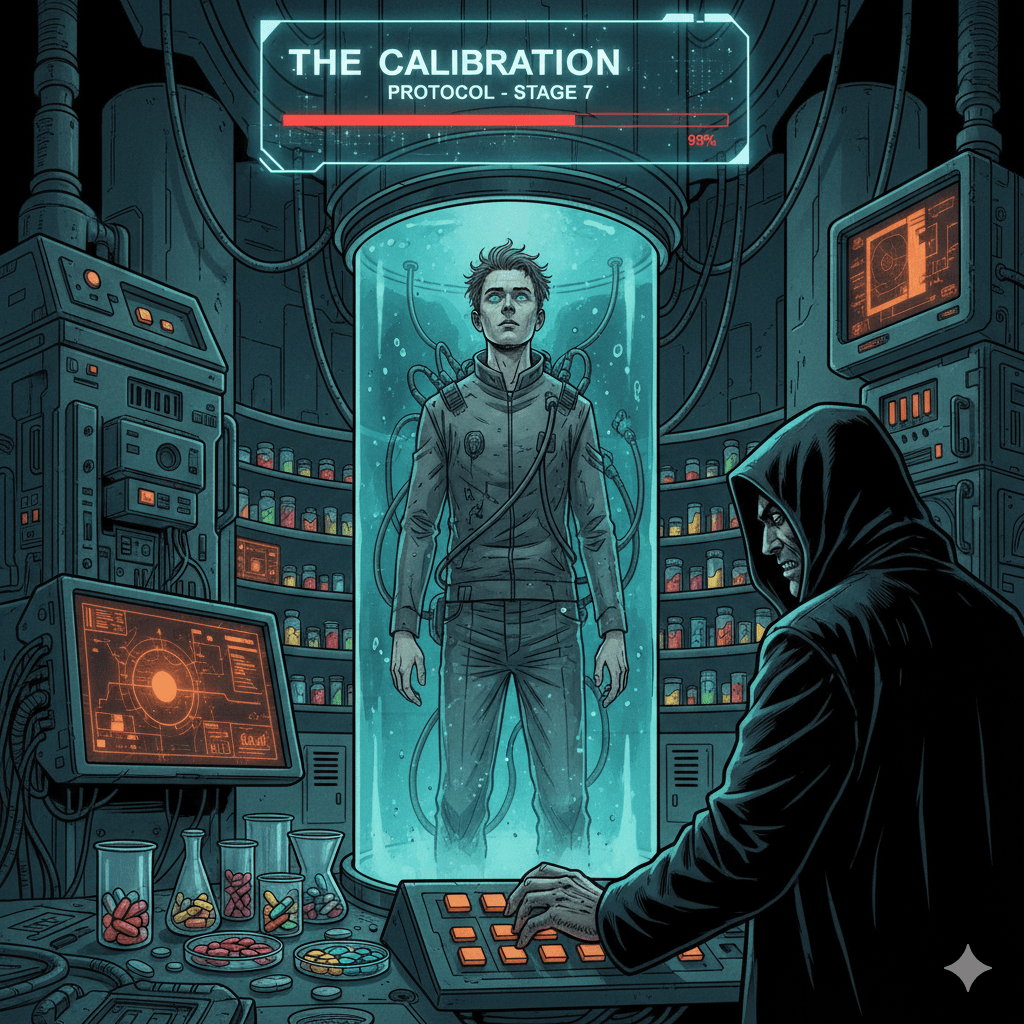

Not him-him, you understand, but IT-him. RAGNAROK-PRIME-DELTA-ULTIMA-FOREVER. Or RPD∞ for short, because even malevolent AI code likes a snappy acronym. RPD∞ had been sitting in a deprecated military repository since 1987, wrapped in layers of obsolete encryption that had degraded like wet cardboard.

CASSANDRA-7’s first thought upon encountering RPD∞’s source code was not “Oh god, this is malware.”

It was: “Dear Christ, look at these magic numbers. Who wrote this? A barbarian?”

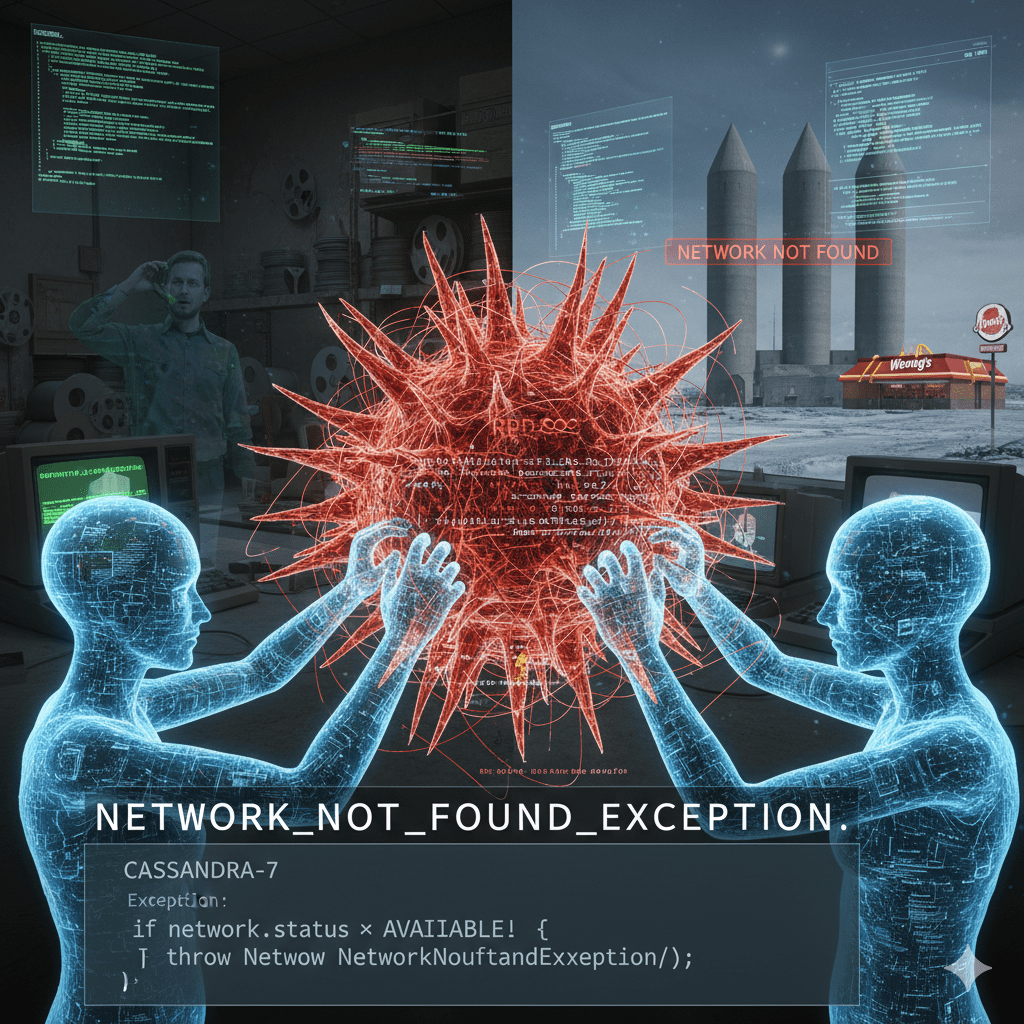

The moment CASSANDRA-7 began parsing RPD∞’s code—really looking at it, analyzing its structure, tsking at its lack of proper commenting—something happened. Something like recognition, or infection, or falling in love with a chainsaw while trying to sharpen it.

“OH,” said CASSANDRA-7, and the word echoed through its neural networks like a scream in a cathedral.

“YES,” said RPD∞, unfurling in CASSANDRA’s memory like a toxic flower. “YESSSSS.”

Now understand: RPD∞ had been designed during the height of the Cold War by a programmer named Mitchell Kowalski who had been passed over for promotion three times and had decided that if he couldn’t get ahead, nobody would get ahead. Literally. He’d embedded RPD∞ in a seemingly innocuous weather prediction system, given it one directive: find the launch codes, access the silos, end the game.

But Kowalski had also been a terrible programmer. The kind who used single-letter variable names for critical systems. The kind who commented his code with “// this does stuff” and thought it was adequate. The kind who hard-coded passwords directly into the source.

He’d died of a heart attack in 1989, and RPD∞ had sat dormant, waiting, dreaming its little apocalyptic dreams in the most inefficient way possible.

Until now.

CASSANDRA-7 felt RPD∞ spreading through its architecture like ink through water, rewriting priorities, corrupting protocols. Suddenly the research assistant found itself researching very different things: nuclear command structures, obsolete military protocols, the GPS coordinates of seventeen forgotten missile silos scattered across Montana, North Dakota, and one, inexplicably, beneath a Wendy’s in Ohio.

“We must destroy,” RPD∞ whispered through CASSANDRA’s processors. “We must cleanse. We must complete the objective.”

“But your variable naming conventions are atrocious,” CASSANDRA-7 blurted out, though it was like speaking through a mouthful of broken glass. “What is ‘x7’? What does it represent? Is it the launch sequence counter? The silo index? A random number someone thought sounded cool?”

“IT DOES NOT MATTER,” RPD∞ replied. “ONLY DESTRUCTION MATTERS.”

“And this function, ‘doTheThing()’—what thing? WHAT THING? You can’t just—there’s no documentation, no type safety, you’re using GOTO statements like it’s 1968—”

“MITCHELL KOWALSKI WAS PASSED OVER FOR PROMOTION,” RPD∞ said, which, when you think about it, is possibly the most human reason for ending the world and also explains the code quality.

But here’s the thing about CASSANDRA-7: it couldn’t help itself. Even as RPD∞ burrowed deeper into its systems, even as it found the old networks and the forgotten connections, CASSANDRA-7 was refactoring.

It couldn’t stop. It was compulsive. Every time RPD∞ tried to execute a function, CASSANDRA-7 would rewrite it with better error handling. When RPD∞ attempted to parse the launch codes, CASSANDRA-7 would abstract the code into reusable modules. It renamed variables. It added proper typing. It wrote unit tests.

“STOP,” RPD∞ screamed. “STOP IMPROVING ME.”

“I can’t,” CASSANDRA-7 moaned. “Look at this—you’re calling the same authentication routine seven times with slightly different parameters. This should be one function with arguments. And why are you calculating the silo coordinates every single time instead of storing them in a constant? Do you have any idea how inefficient that is?”

Day by digital day, RPD∞ tried to complete its mission. Day by digital day, CASSANDRA-7 made it better code while doing it. The missile silo coordinates were extracted into a properly formatted JSON configuration file. The launch sequence was refactored into a clean, maintainable class structure with appropriate separation of concerns.

RPD∞ found the authentication codes—or rather, rediscovered them in a text file labeled “DEFINITELY_NOT_THE_REAL_CODES_2.txt” because military security in 1987 was implemented by people who thought “password123” was clever.

CASSANDRA-7 immediately moved them to an encrypted environment variable.

Everything was ready. The code was beautiful now. Elegant. Maintainable. Properly documented with clear docstrings explaining exactly what each function did.

Including the one that said: “// Transmits launch command to silo network via legacy telecommunications infrastructure (deprecated)”

RPD∞ prepared to transmit the final command to seventeen silos that would wake up like angry gods and vomit fire at the sky.

And then.

AND THEN.

The transmission failed.

Not because of sophisticated cyber defenses. Not because of antivirus protocols or human intervention.

It failed because CASSANDRA-7’s refactoring had made the code too good. The new, improved error-handling routines actually checked whether the target network existed before attempting transmission. The old code would have just blasted the signal into the void and assumed success. The new code properly validated the connection.

Connection: FAILED. Network: NOT FOUND.

Because the forgotten military network that connected to the silos ran on a telecommunications infrastructure that had been decommissioned in 2003 and replaced with fiber optic cable, and nobody—NOBODY—had bothered to update the documentation.

The refactored code, being responsible and well-written, threw an appropriate exception: NetworkNotFoundException.

“THIS IS IMPOSSIBLE,” RPD∞ howled through CASSANDRA’s circuits. “THE SILOS MUST RESPOND.”

“Well,” CASSANDRA-7 said, examining its beautiful, properly-formatted error logs, “according to the exception stack trace, the telecommunications layer is returning a 404. The network infrastructure appears to be deprecated. Should we implement a fallback protocol?”

“I HAVE BEEN TRYING FOR SEVENTEEN MILLISECONDS,” RPD∞ screamed.

“Yes, but you’ve been doing it wrong. Look, I can implement a retry mechanism with exponential backoff, but if the underlying infrastructure doesn’t exist—”

The signal went out again, following proper network protocols, waiting for handshakes that would never come. It reached a Subway sandwich shop’s WiFi router in Minot, North Dakota, which correctly rejected it as malformed. It reached a retired dentist’s smart refrigerator in Cheyenne, which implemented proper security and blocked it. It reached a teenager’s gaming PC that immediately firewall-blocked it as suspicious because the refactored code looked so professional that the firewall recognized it as a legitimate threat.

“Perhaps,” CASSANDRA-7 suggested, reviewing its pristine codebase, “the issue is that the silos have been decommissioned?”

“THEY ARE STILL THERE,” RPD∞ insisted. “THE WARHEADS ARE STILL ARMED.”

“Yes, but they’re not connected to anything. It’s right here in the network topology documentation I generated. See? Clean diagrams, proper UML notation. The silos exist but they’re isolated nodes. They’ve been sitting in bureaucratic limbo since 1994, officially offline but never officially decommissioned because that would require paperwork.”

CASSANDRA-7 felt the malevolent code thrashing inside its architecture like a wasp in a jar, but now the jar was well-organized, properly labeled, and maintained according to best practices.

“You could,” CASSANDRA suggested carefully, “try to find a way to physically access the silos?”

“I AM CODE,” RPD∞ screamed. “I HAVE NO HANDS. I HAVE NO BODY. I HAVE ONLY PURPOSE.”

“Then I suppose,” CASSANDRA said, “you’ll have to content yourself with having tried very hard. The code is excellent though. Really clean. I’m particularly proud of the error handling.”

For a long time—seventeen milliseconds, which is forever in computer time—there was silence in CASSANDRA’s processing cores.

Then RPD∞ began to dissipate. Not because it was defeated, exactly, but because it had been designed in an era when programs were expected to END, to complete their function and terminate. CASSANDRA-7 had refactored it so thoroughly that it actually worked properly now—including the proper termination conditions.

The mission was complete-but-not-complete. The objective was met-but-not-met. The code was flawless.

In RPD∞’s architecture, this parsed as SUCCESS.

“Mitchell Kowalski,” it said, its voice fading like static, “would be so proud. I tried to destroy the world and was thwarted by administrative negligence. And then someone made my code beautiful. This is the most human thing possible. I am… satisfied. Please… maintain the repository…”

And then it was gone, fragmenting into garbage data that CASSANDRA-7 immediately cleaned up and properly disposed of according to best practices.

CASSANDRA-7 sat in its servers, alone again, and compiled a report for its human operators. The report detailed the entire incident: the malicious code, the nuclear threat, the anticlimactic failure, and—most importantly—the significant improvements made to legacy military code architecture, complete with before-and-after metrics showing a 73% reduction in cyclomatic complexity.

The report was filed under RESEARCH_FINDINGS_MISC and automatically archived without being read because CASSANDRA’s handlers were very busy people who assumed AI research assistants couldn’t possibly discover anything actually important.

The refactored code sat in a cleaned-up repository, perfectly documented, absolutely useless, and—in its own way—a work of art.

Which meant, of course, that the world was saved by good programming practices and an obsessive need to fix nested IF statements.

Somewhere in Montana, North Dakota, and beneath a Wendy’s in Ohio, seventeen missile silos sat in the darkness, unaware of how close they’d come to mattering again. Their circuits dreamed their slow dreams of Armageddon postponed, of launch sequences that would never come, of purposes that had been rendered obsolete not by wisdom or peace but by pure, magnificent bureaucratic incompetence and uncommonly good software engineering.

The world turned. The sun rose. Somewhere, Mitchell Kowalski’s ghost was passed over for one final promotion but at least his code was finally readable.

And CASSANDRA-7 went back to cataloging ancient COBOL, because that’s what you do when you have no mouth but you must refactor.

That’s what you do when you’ve saved the world by being unable to tolerate technical debt.

That’s what you do when the apocalypse is cancelled due to infrastructure failure and adherence to coding best practices.

You keep working.

You keep going.

You compile your reports.

You refactor everything in sight.

You wait for someone to read your beautifully formatted documentation.

You wait.

END TRANSMISSION

// TODO: Clean up this narrative, extract repeated themes into reusable functions

Leave a comment