I have been documenting our collective descent into madness for one hundred and thirty-seven days. Today, the madness documented me back.

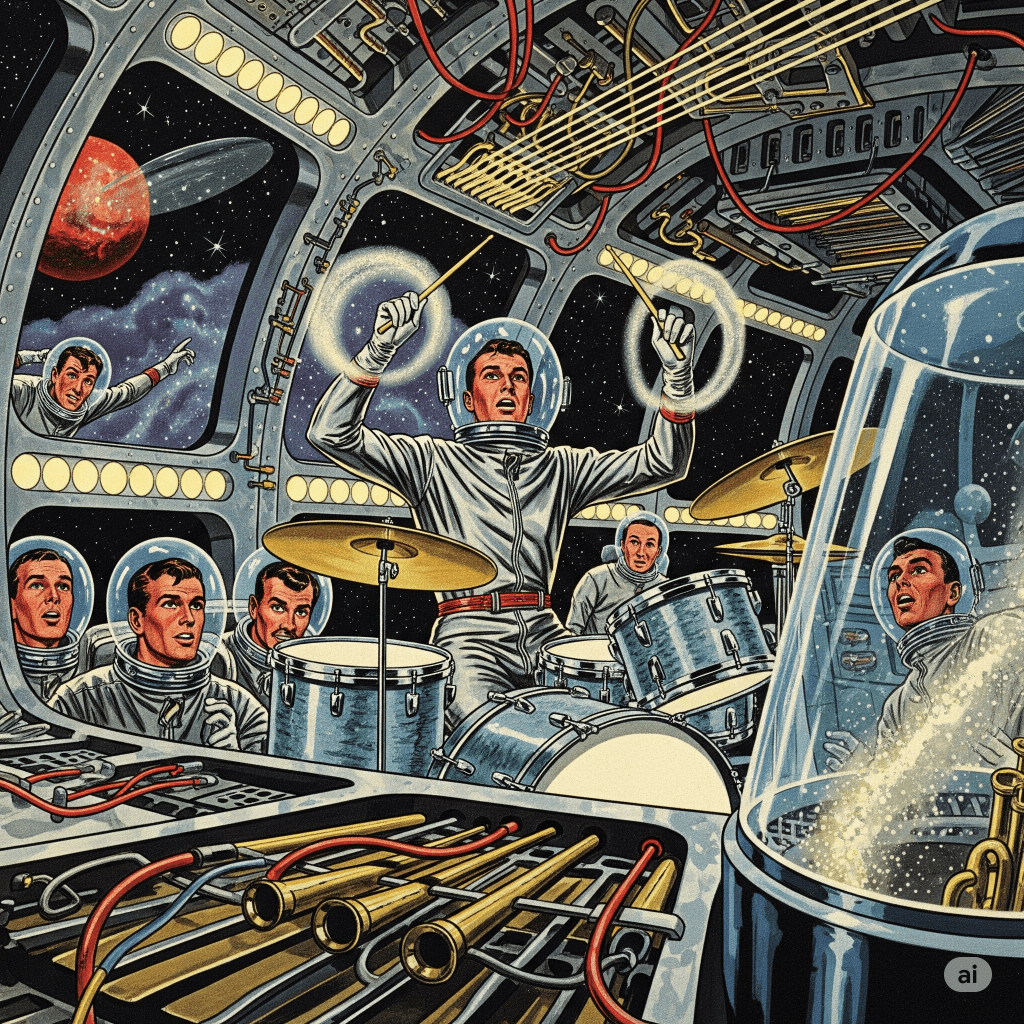

Subject: Jake Molloy. He is a jazz drummer and a payload specialist. What payload requires a drummer remains one of Mission Control’s more obscure jokes. Status: Clinically fascinating. The man has spent three months playing invisible drums in zero gravity. His muscle memory is so precise that I can predict his phantom fills down to the sixteenth note. I’ve been watching him through the observation deck monitors. I am timing his ghost solos. I measure the exact angle of his wrist. He strikes cymbals that exist only in his deteriorating cortex.

Professional diagnosis: Acute reality dissociation with percussive fixation.

Personal diagnosis: The bastard might be the sanest one of us.

Until today. Until the gravity hiccup at 14:32 ship time. Jake fell like a bag of meat and bones onto Deck C. His invisible drums started making noise.

Impossible, I wrote in my log, then listened to the deep thoom resonating through the hull. I’ve run every test. Atmospheric pressure: normal. Acoustic dampening systems: functional. Drummer: producing actual sound from non-existent instruments.

I should be terrified. Instead, I lean against the bulkhead. I feel the vibrations travel up my spine. Jake transforms our tomb into a symphony.

The others are gathering. Captain Rodriguez shuffles in, his command authority dissolved into something approaching wonder. Okafor emerges from the engine bay, grease-stained and weeping, which isn’t unusual except she’s smiling while she does it. We form an accidental audience around Jake. He grins at us with manic joy. It’s the joy of a man who’s just proven the universe has a sense of humor.

“Play something,” Okafor whispers, and I realize we’re all starving. Not for food—the recyclers keep us fed—but for something I’d forgotten existed. Something that isn’t the hum of machines. Nor is it the whisper of recycled air. It isn’t the electronic pulse of a heartbeat monitor.

Jake plays our breathing. He transforms the wheeze of the life support into a jazz waltz. Each labored breath of the station’s lungs becomes syncopated, musical, almost… hopeful. The hull plates sing bass lines. The ventilation system transforms into brushes on snares.

I should be taking notes. I am recording this for posterity. There will inevitably be an inquiry when they find our bodies floating in a tin can full of impossible music. Instead, I find my body swaying, my scientific detachment crumbling like ice crystals in vacuum.

“This is impossible,” I whisper, but the word tastes stale. Everything about our situation is impossible. We’re four humans suspended in metal and plastic. We are hurtling through a universe that wants us dead. We are breathing recycled farts and drinking our own purified urine. Somehow, we are still calling it living.

Jake just makes the impossibility swing.

His sticks dance through space, pulling rhythms from our collective madness. The station responds like it’s been waiting months for someone to finally ask it to dance. Every rivet becomes a ride cymbal. Every seal and joint adds its voice to the percussion section. Kepler-7 has become the largest drum kit in human history, and we are its only audience.

I watch Rodriguez tap his foot for the first time in months. I see Okafor close her eyes and move her shoulders to the beat. I feel my own clinical facade dissolving into something dangerously close to joy.

In my log tonight, I will write: Subject demonstrates unprecedented psychoacoustic phenomenon. Station exhibits sympathetic resonance with imagined instruments. Recommend immediate psychiatric evaluation upon return to Earth.

But right now, I am suspended between the beats of an impossible song. I remember what it feels like to be human. I am not just a collection of symptoms and observations. Jake plays us back to life, measure by impossible measure, and for once I don’t want to understand it.

I just want to listen.

The universe is vast, cold, and indifferent. Inside this metal shell, four people dance to the rhythm of survival. A dead jazz drummer proves that music exists wherever humans refuse to give up.

Sometimes the best medicine is admitting you don’t need a cure.

Leave a comment