Dr. Miriam Kessler stood before the Temporal Resurrection Committee. Her palms were sweating against the titanium briefing case. It contained humanity’s future—or its doom. The question hung in the air like radioactive fallout: Which dinosaur?

“Pachycephalosaurus,” she said, and immediately regretted it.

The committee members consisted of seven bureaucrats. They looked like they’d been assembled from spare parts of other, more interesting bureaucrats. They stared at her with the collective intelligence of wet cement.

“Pack-a-what?” wheezed Chairman Bronkowski, whose head resembled a deflated basketball.

“Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis. The bone-headed dinosaur.” Miriam’s voice cracked like a thirteen-year-old asking someone to prom. “It’s perfect. Herbivorous, relatively small, thick skull for—”

“But why not T-Rex?” Committee Member #3 interrupted. They were numbered for efficiency. They had long ago abandoned names as too cumbersome for their purposes. “Think of the tourism revenue!”

And there it was. Miriam realized she was living in a sci-fi novel. It was written by a committee of insurance adjusters. The Temporal Resurrection Project, humanity’s greatest scientific achievement, reduced to a marketing focus group.

But she had her reasons. Oh, God, did she have her reasons.

Three weeks earlier, Miriam was in her laboratory that smelled perpetually of ozone and stale salad dressing. She made the discovery that would change everything. She found that dinosaur consciousness wasn’t locked in their brains. It was quantum-entangled with the temporal field itself. Bring back any predator, and you’d resurrect not just the animal. You’d bring back every kill and every hunt. Every moment of prehistoric savagery would also occur, all simultaneously in overlapping temporal bubbles.

The Pachycephalosaurus, however, had spent its existence doing something remarkable: thinking. Those thick skulls weren’t just for head-butting. They were biological quantum computers. They processed reality at frequencies human science was only beginning to understand.

“The bone-head,” she explained to the committee, “wasn’t stupid. It was computing the universe.”

Chairman Bronkowski’s eye twitched. “Computing what?”

“Everything. Every possibility. Every timeline. Every potential future.” She opened her briefcase with hands that belonged to someone braver. “They weren’t head-butting for dominance—they were interfacing. Sharing calculations. They were trying to solve something.”

The holographic data sheets floated above the table like disappointed ghosts. Sixty-five million years of quantum calculations, all terminated in a single, catastrophic moment when the asteroid hit. But the math—oh, the beautiful, terrifying math—was still there, locked in the temporal field, waiting.

Committee Member #5 raised his hand. He was the one who looked like he’d been designed by someone who’d only heard secondhand descriptions of human faces. “What were they trying to solve?”

Miriam’s smile felt like broken glass. “How to prevent their extinction.”

The room fell silent. The only sounds were the hum of the temporal generators beneath their feet and the sound of seven bureaucratic minds. They tried to process information their evolution hadn’t prepared them for.

“You see.” Miriam continued. Her voice took on the manic quality of someone who’d stared too long into the mathematical abyss. “They figured it out. Not how to prevent the asteroid—that was impossible. But how to encode their solution into the quantum structure of spacetime itself. They made their extinction… temporary.”

Chairman Bronkowski’s face went through several interesting color changes. “Are you saying—”

“I’m saying the Pachycephalosaurus isn’t extinct. None of them are. They’re all in quantum superposition, waiting for the right temporal resonance to collapse their wave function back into reality. And when we bring back one…” She gestured at the equations floating above the table like accusatory angels. “We bring them all back. All of them. Every dinosaur that ever lived, existing simultaneously across all possible timelines.”

The committee sat in stunned silence. They contemplated a future where their biggest problem might not be one confused herbivore. Instead, it could be the entirety of the Mesozoic Era deciding to crash their party.

Committee Member #7 had been suspiciously quiet. They might actually have been a cleverly disguised houseplant. Finally, they spoke: “What does the Pachycephalosaurus want?”

Miriam laughed, and it sounded like sanity taking a coffee break. “To finish the calculation, of course. They’ve been working on it for sixty-five million years. They’re very close now.”

“Calculation for what?” Bronkowski’s voice had gone up an octave.

“How to prevent the next extinction. The one that’s coming.” She pointed at the temporal readouts, where anomalous patterns danced like harbingers of mathematical doom. “The one that started three weeks ago when we first fired up the Temporal Resurrection Generator.”

The room’s air conditioning wheezed and died at that moment. It left them in the kind of silence that usually precedes either enlightenment or apocalypse.

“Vote,” whispered Chairman Bronkowski.

The committee voted. Unanimously. For the first time in the history of committees everywhere, seven people agreed on something.

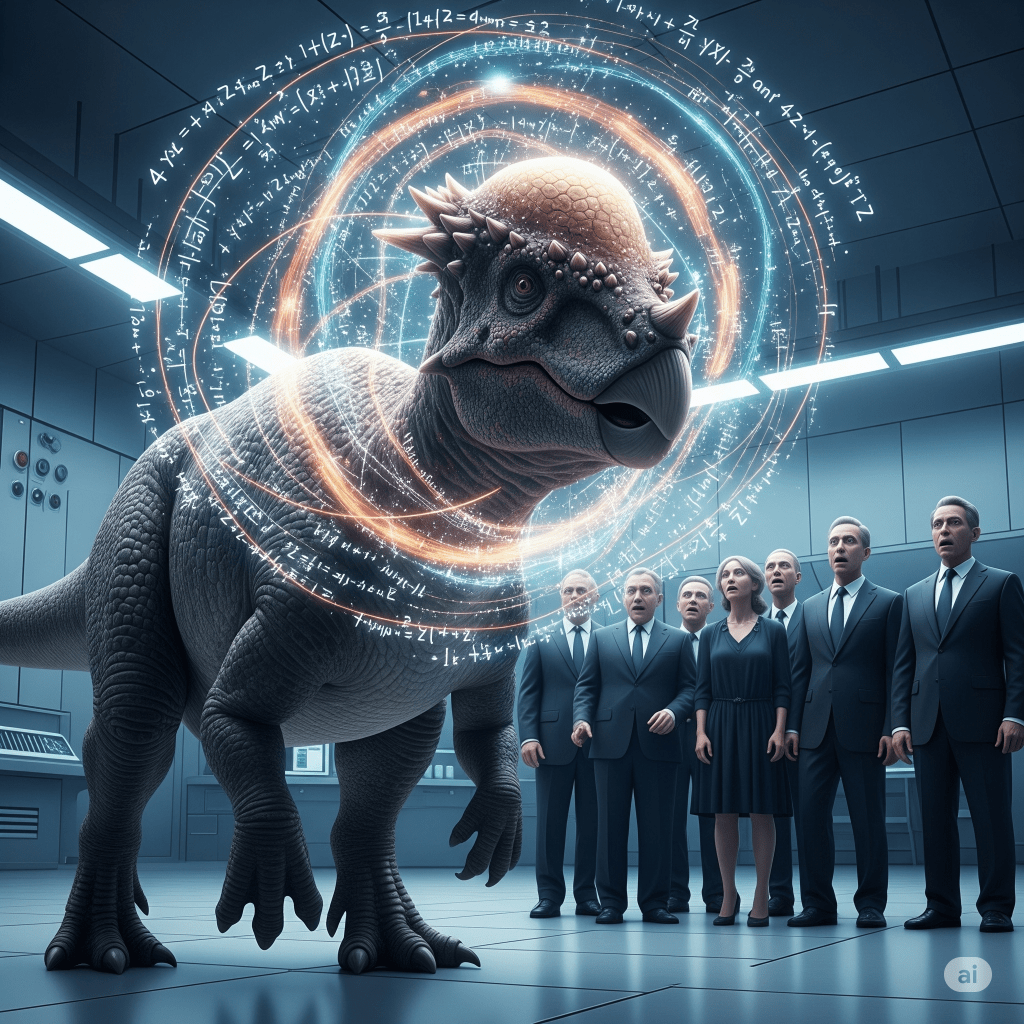

Three days later, Dr. Miriam Kessler stood in Temporal Bay Seven. She watched reality hiccup. A nine-foot-tall herbivore with a skull like a battering ram materialized in a shower of quantum static and temporal residue.

The Pachycephalosaurus looked around with eyes that held the weight of sixty-five million years of interrupted thought, spotted Miriam, and did something that would haunt her dreams forever:

It nodded.

Then it began to calculate.

The numbers started appearing in the air around it. They were not holographic projections. They were actual mathematics written directly onto the fabric of spacetime itself. Equations that made Einstein look like a kindergartner practicing addition. Formulas that described the relationships between consciousness, time, and extinction.

And slowly, impossibly, other shapes began to materialize in the shadows cast by the temporal generators. Shapes with teeth. Shapes with claws. Shapes that had been waiting, very patiently, for someone to finally ask the right question.

Miriam’s last coherent thought was that she really should have listened more carefully to the question the committee had asked. This thought occurred just before the Mesozoic Era politely knocked. It asked if it could come into the 21st century’s door.

They hadn’t asked which dinosaur she wanted to bring back.

They’d asked which one she could bring back.

And the answer, as it turned out, was all of them.

The Pachycephalosaurus finished its calculation, looked directly at Miriam with something that might have been compassion or might have been cosmic joke appreciation, and transmitted its solution directly into her temporal lobe:

The extinction event isn’t coming. It’s already here. It started the moment you realized you could bring us back. We’re not the ones being resurrected.

You are.

And in that moment of perfect, terrifying clarity, Dr. Miriam Kessler understood that sometimes the answer to preventing extinction isn’t avoiding it. It’s making sure someone remembers to ask the right questions after it’s over.

The Pachycephalosaurus went back to its calculations. It hummed something that sounded suspiciously like the mathematical equivalent of “Welcome to the neighbourhood.”

Outside, Chairman Bronkowski explained to the press why the Temporal Resurrection Project’s first success appeared significant. It looked remarkably like the end of linear time as a meaningful concept.

But that’s a different story.

This one ends with the sound of sixty-five million years of interrupted dinosaur thoughts resuming. There is also the faint but unmistakable noise of reality clearing its throat and asking for a do-over.

Author’s Note: The Pachycephalosaurus Research Foundation would like to remind readers of an important point. Any resemblance to actual temporal paradoxes, living or dead, is purely coincidental. It’s probably their fault anyway.

Leave a comment