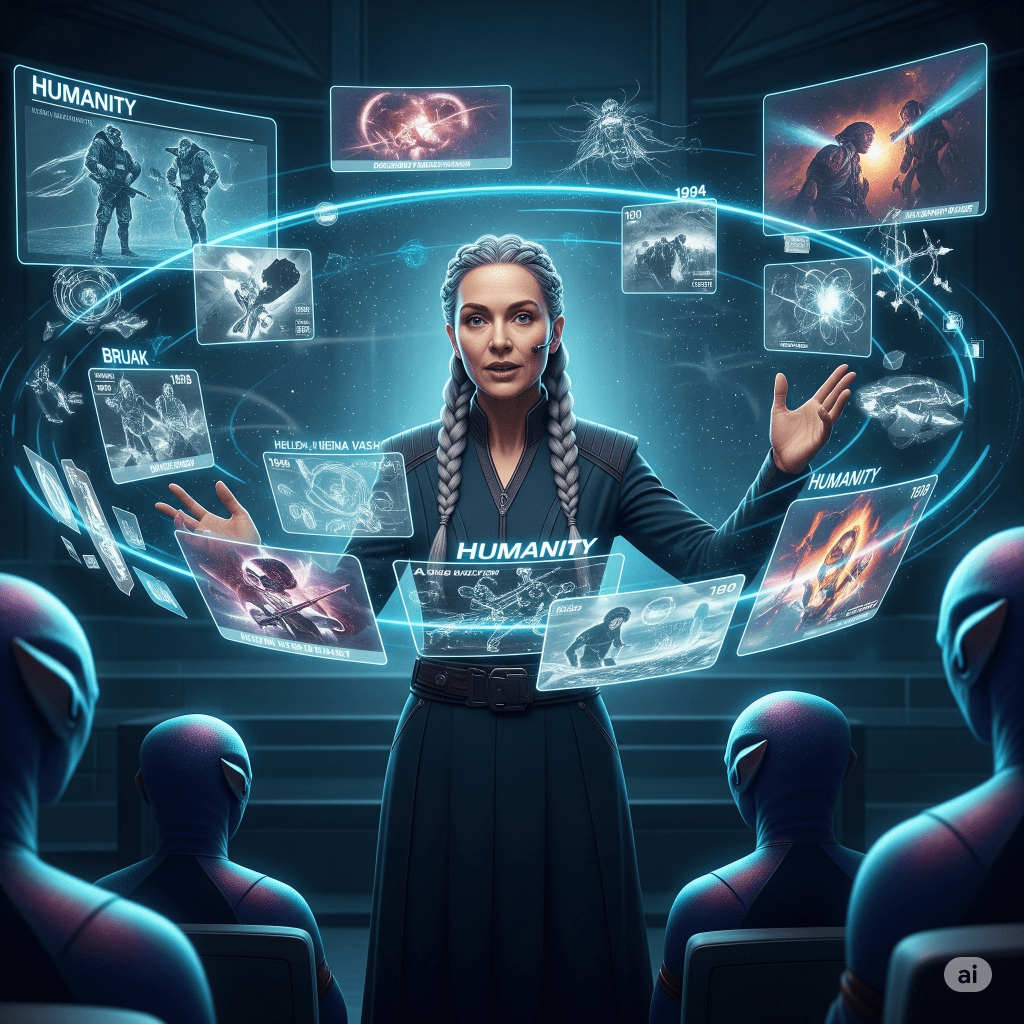

Professor Helena Vash adjusted the neural interface behind her left ear, feeling the familiar electric tingle as her consciousness synced with the Zephyrian lecture hall’s empathic broadcast system. Six hundred alien minds pressed against her awareness like curious moths against a window—each one a kaleidoscope of shifting geometries and colors that human language had no words for.

“Today,” she began, her voice carrying across dimensions of understanding that shouldn’t exist, “I will tell you about the monkeys who learned to dream of stars.”

The Zephyrians rippled with what might have been amusement, their crystalline forms refracting the artificial sunlight of their homeworld into prismatic cascades. She could feel their skepticism bleeding through the neural link—this small, soft creature from the third planet of an unremarkable star, claiming to speak for a species that had somehow clawed its way across the galaxy.

Helena smiled grimly. If they only knew.

“Homo sapiens,” she continued, allowing the Latin to roll off her tongue like an incantation, “emerged approximately three hundred thousand years ago on what we now call Old Earth. But emergence—that’s the wrong word, isn’t it? Suggests something clean, purposeful. No, we erupted from the African savanna like a virus with delusions of grandeur.”

She gestured, and the holographic display bloomed with images—apes descending from trees, fire flickering in primitive caves, the first crude stone tools. The Zephyrians’ attention sharpened; she could feel their collective focus like pressure behind her eyes.

“We were not the strongest. We were not the fastest. We were barely clever enough to avoid being eaten by our betters. But we had something else—something that would prove to be both our salvation and our curse.” She paused, letting the neural link carry the weight of her words. “We were dissatisfied.”

The display shifted, showing the spread of humanity across continents, the rise and fall of civilizations, the endless cycle of creation and destruction that marked the human story.

“Other species on Earth found their niche and stayed there, content. We found paradise and immediately began plotting how to burn it down and build something different in its place. We were the only animal that could look at the Garden of Eden and think, ‘This place needs better lighting.’”

A pulse of confusion from the Zephyrian collective. Helena felt their bewilderment at the concept—why would any rational being destroy something beautiful?

“Because,” she said, reading their unspoken question through the link, “beauty was never enough. We needed meaning. We needed purpose. We needed to matter in a universe that seemed specifically designed to remind us how small and temporary we were.”

The hologram showed the development of agriculture, the birth of cities, the first tentative steps toward civilization. But Helena’s narrative voice carried an undercurrent of something darker.

“We learned to grow food, but that wasn’t enough—we had to grow better food, different food, food that would make us superior to our neighbors. We learned to build shelters, but that wasn’t enough—we had to build monuments, temples, towers that would scrape the belly of heaven itself. We learned to make tools, but that wasn’t enough—we had to make weapons, because the fastest way to get what you want is to take it from someone who already has it.”

The images became more complex now: the rise of empires, the development of writing, mathematics, astronomy. But also war, slavery, the systematic destruction of those who stood in the way of human ambition.

“We mapped our world and found it wanting. We looked up at the stars and decided they belonged to us. We split the atom and asked ourselves, ‘What else can we break that seemed unbreakable?’ We built machines to think for us, then worried they might do it better than we could.”

Helena felt a tremor through the neural link—fear, perhaps, from creatures who had never known such relentless, self-destructive ambition.

“By the 21st century of our Common Era, we had poisoned our atmosphere, acidified our oceans, and driven thousands of species to extinction. We had weapons capable of sterilizing entire continents and entertainment systems sophisticated enough to make us forget why we built them. We stood on the precipice of either transcending our origins or destroying ourselves completely.”

The display showed the chaos of the early space age—primitive rockets, failed colonies, the first tentative steps beyond the cradle world.

“And then,” Helena said, her voice dropping to almost a whisper, “we made the choice that defines us still. We looked at our dying world, our fractured societies, our endless capacity for cruelty and destruction, and we said: ‘Not enough. We can do worse.’”

The Zephyrians recoiled, their crystalline forms darkening with what Helena had learned to recognize as horror.

“We didn’t just leave Earth—we fled it, carrying our contradictions and compulsions with us. We spread across the solar system like a plague of conscience, terraforming worlds not because we needed them, but because we needed to prove we could. We built generation ships and launched them at distant stars, not knowing if anyone would survive the journey, not caring as long as something of us persisted.”

The hologram expanded, showing the great diaspora—sleeper ships carrying frozen dreamers to distant suns, quantum tunneling devices that punched holes through reality itself, the gradual colonization of a thousand worlds.

“We found other species,” Helena continued, “and we did what we always do. We studied them, catalogued them, tried to understand them. And then we either tried to save them or tried to exploit them, sometimes both at the same time, because we’ve never been able to meet another consciousness without trying to make it more like us.”

She gestured toward her alien audience. “Even now, standing before you, part of me is taking notes, wondering how your society works, what we might learn from you, how we might improve you. It’s not malice—it’s worse than malice. It’s love. We want to help everyone become the best possible version of themselves, even if they were perfectly fine the way they were.”

The neural link carried waves of complex emotion from the Zephyrian collective—fascination, revulsion, something that might have been pity.

“We are now spread across sixteen thousand star systems. We have built worlds from scratch, resurrected dead planets, created artificial suns. We have encountered forty-seven different sapient species and established peaceful relations with forty-six of them.” She paused. “The forty-seventh no longer exists, not because we destroyed them, but because we tried so hard to help them that they ceased to be themselves.”

Helena felt the weight of that admission settle over the lecture hall like a shroud.

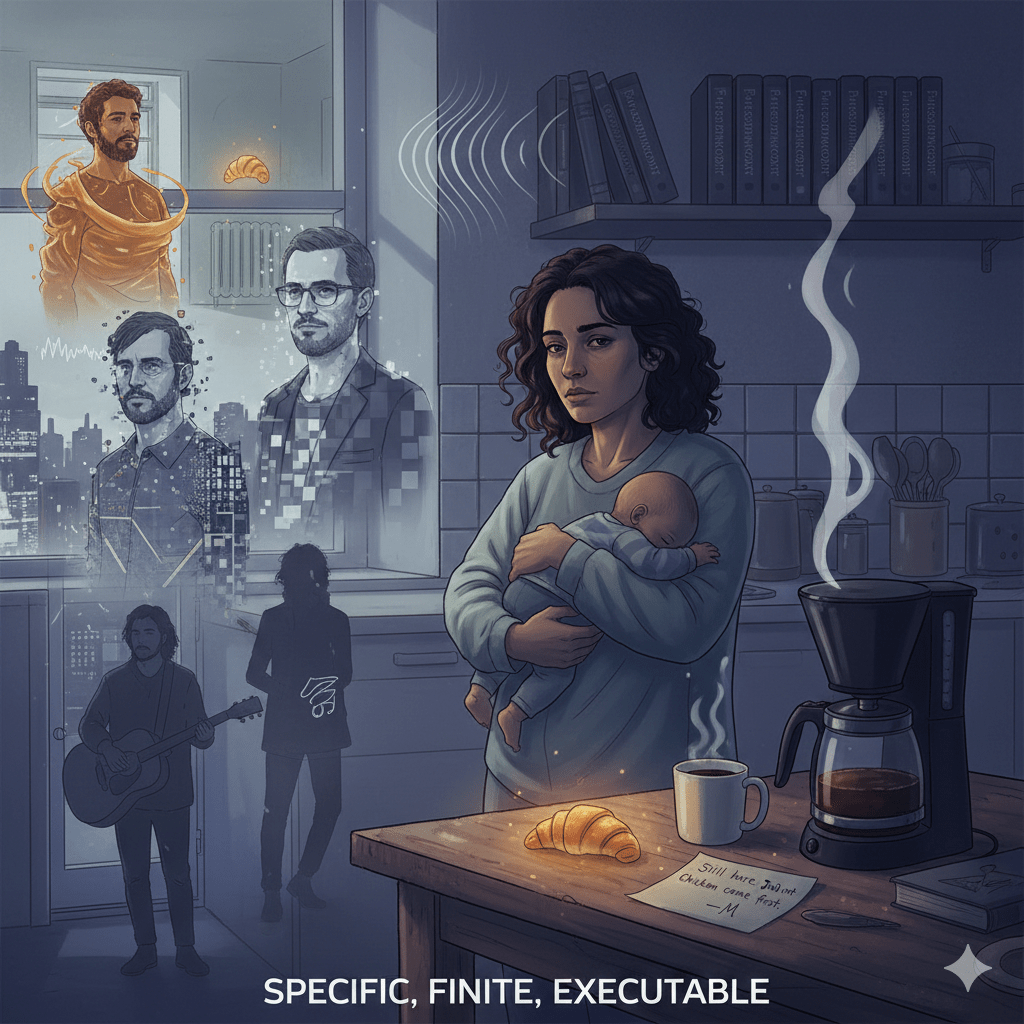

“We have cured death, more or less. We have solved scarcity, mostly. We have eliminated war between humans, although we’ve replaced it with something arguably worse—an endless, exhausting peace in which everyone is constantly trying to perfect everyone else.”

The display showed the contemporary human worlds: gleaming cities that grew like coral, space habitats that spun like prayer wheels, the vast engineering projects that marked humanity’s passage through the galaxy.

“We have become gods, of a sort. And we hate it, because gods are supposed to be satisfied, and satisfaction is the one thing we have never learned to achieve. We look at our paradise and we see only its flaws. We look at our immortality and we mourn our lost mortality. We look at our vast knowledge and we weep for our vanished innocence.”

Helena turned away from the display to face her alien audience directly.

“That is what I am here to tell you about humanity. We are the species that achieved everything we ever dreamed of and then spent the next thousand years explaining why it wasn’t good enough. We are the animals who learned to build heaven and then complained about the acoustics.”

The neural link carried a long moment of stunned silence.

“But,” she said, and her voice carried a note of something that might have been hope, “we are also the species that never, ever gives up. We fail constantly, spectacularly, inevitably. We disappoint ourselves, we disappoint each other, we disappoint the universe itself. And then we get up, dust ourselves off, and try again.”

She gestured at the images of human achievement surrounding them.

“Every one of these worlds, every one of these cities, every one of these impossible dreams made manifest—they exist because some human somewhere looked at failure and said, ‘Not today.’ We are the species that treats impossibility as a starting point for negotiations.”

Helena felt something shift in the Zephyrian collective consciousness—a grudging respect, perhaps, or maybe just a deeper understanding of the strange creatures who had somehow stumbled their way across the galaxy.

“So when you ask me to explain humanity,” she concluded, “this is what I tell you: We are the dissatisfied gods of a universe we cannot help but try to improve. We are the dreamers who dream of better dreams. We are the broken children of a broken world who somehow learned to make beautiful things from the fragments.”

She paused, feeling the weight of six hundred alien minds processing her words.

“And we are still here, still dreaming, still trying, still failing, still beginning again. Because that’s what humans do. We endure.”

The lecture hall fell silent except for the distant hum of alien machinery. Helena disconnected from the neural link, suddenly aware of her own small, fragile humanity in this place of crystal and light.

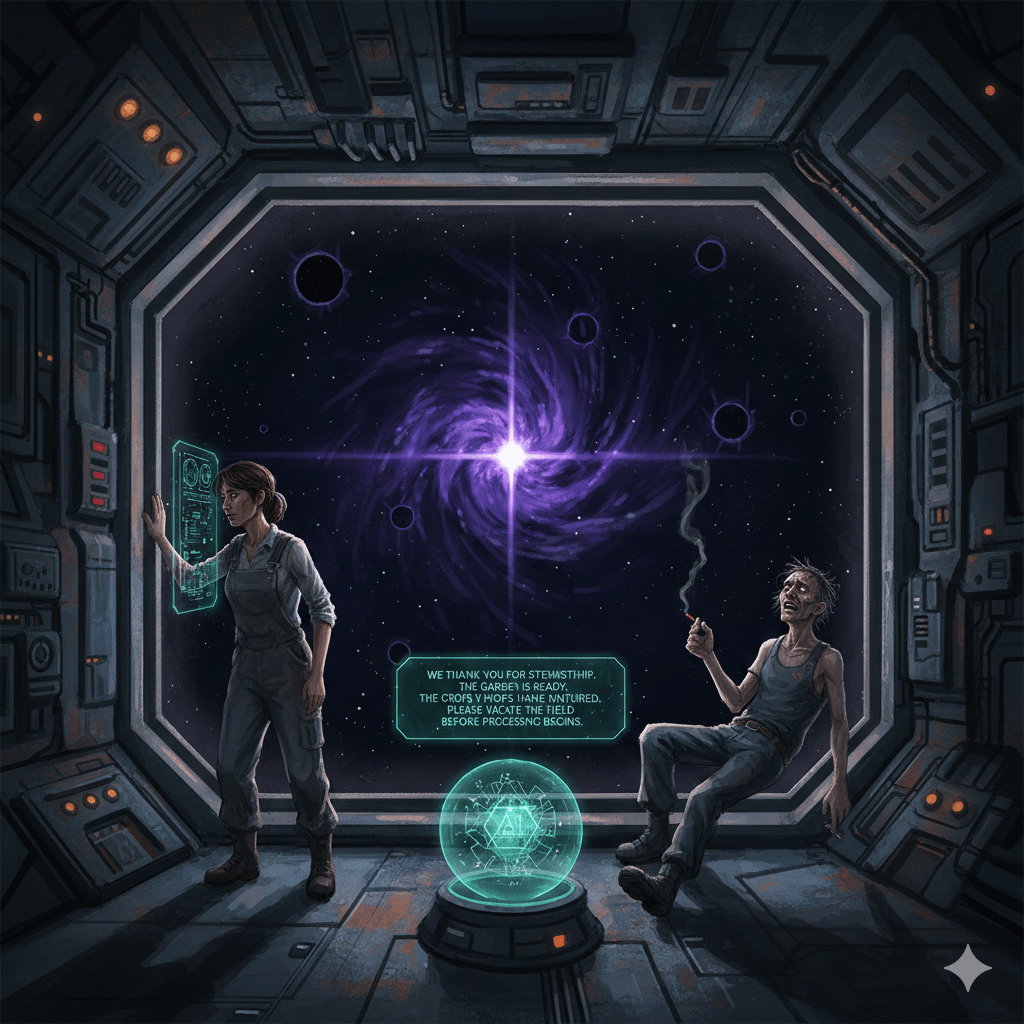

One of the Zephyrians approached her afterward, its form shifting through spectrums of meaning she couldn’t quite grasp.

“Professor Vash,” it said in its resonant, multi-tonal voice, “I have one question.”

“Yes?”

“Given everything you have told us about your species—your destructiveness, your dissatisfaction, your endless capacity for both creation and catastrophe—why should we trust you?”

Helena looked out through the transparent walls of the lecture hall at the alien sky, where two suns cast competing shadows across a landscape that had never known human footsteps.

“Because,” she said, “we’re the species that asks that question about ourselves. We’re the only gods who doubt their own divinity. And doubt, my friend, is the beginning of wisdom.”

The Zephyrian’s form rippled with what she had learned to recognize as deep thought.

“That,” it said finally, “is either the most terrifying thing I have ever heard, or the most hopeful.”

Helena smiled. “Yes,” she said. “Exactly.”

Leave a comment