I am seventeen cycles old and my body is forgetting how to hold itself together.

This is not the way my people usually die. We dissolve gradually over many centuries, our consciousness expanding until we become one with the electromagnetic fields that dance between stars. But I am dissolving too quickly, my cellular matrices flickering in and out of phase like a badly tuned radio seeking a signal that no longer exists.

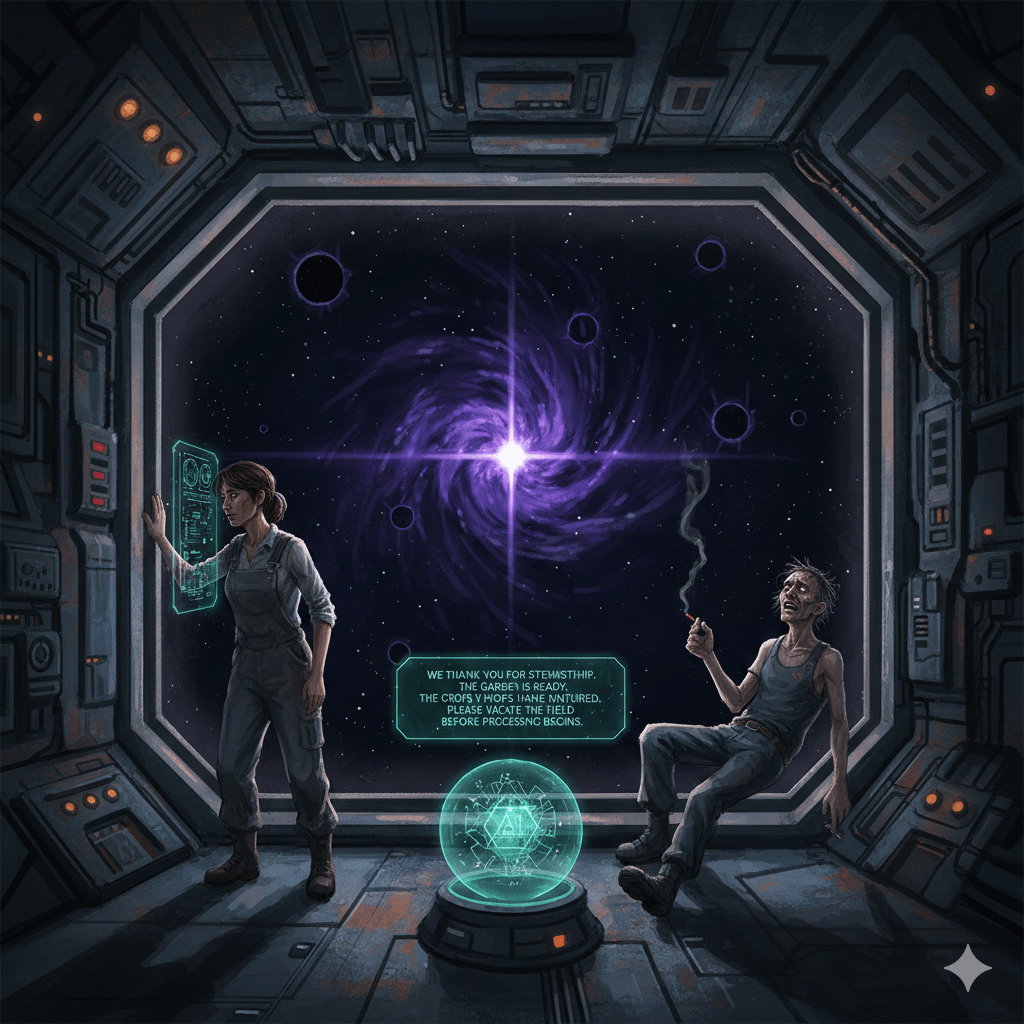

The humans call this place Hippocrates Station, though the name translates poorly into my harmonic language. When I try to speak it, the frequencies create small tears in the fabric of space-time, which Dr. Elena finds “concerning” but “fascinating.” She uses both words often, usually in that order.

Dr. Elena is my favorite human. She has learned to modulate her voice to frequencies that don’t cause me physical pain, and she never looks directly at me when I’m phasing through dimensions that hurt human eyes to perceive. More importantly, she treats me as if I will live, even when the probability matrices suggest otherwise.

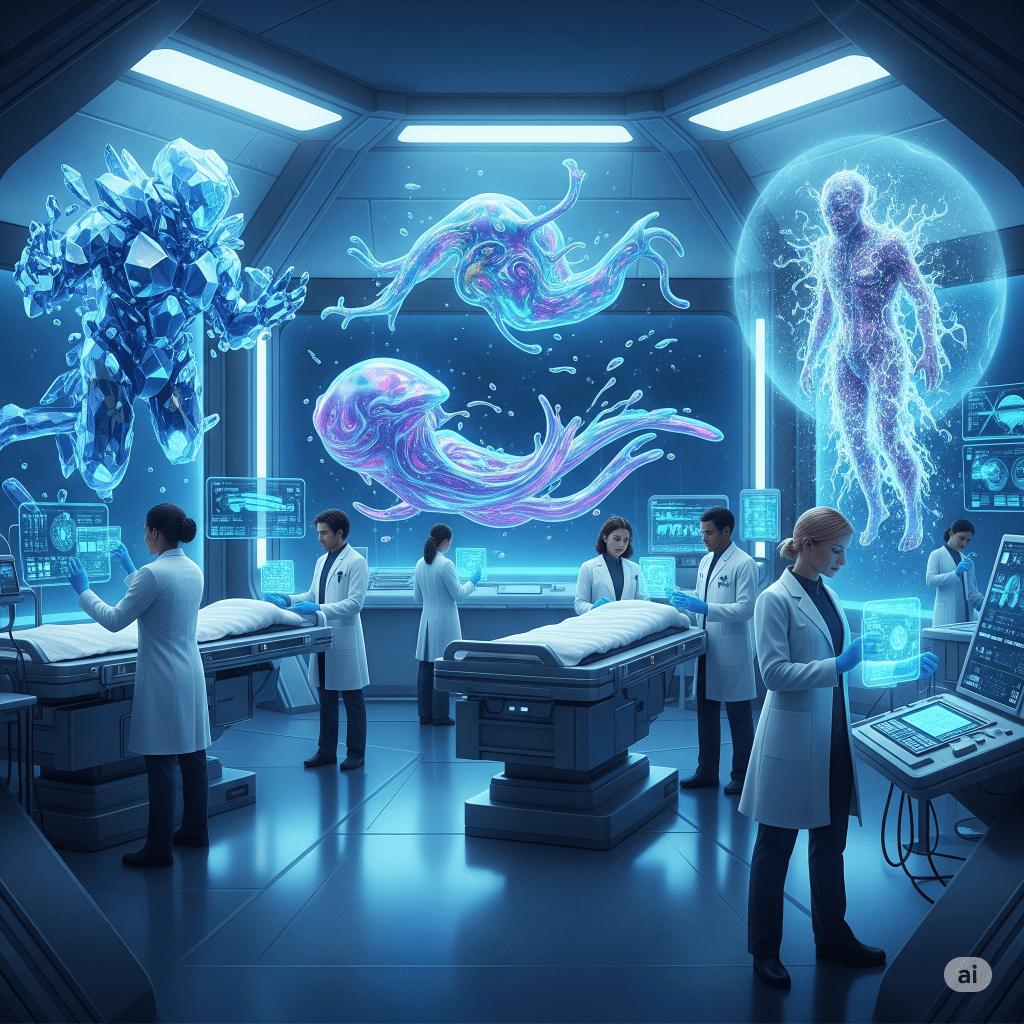

The other patients here are strange and wonderful. In the chamber next to mine, a being made of crystallized starlight hums mathematical equations that solve themselves in the air. Across the corridor, a creature that exists as both liquid and gas simultaneously tells stories that change depending on who is listening. There is a collective intelligence that communicates by rewriting local reality, turning the walls briefly into gardens or filling the air with butterflies made of pure mathematics.

We are all dying in ways our species never evolved to die.

The trouble began when the ships stopped coming. For months, we had watched vessels arrive with supplies, new medical equipment, replacement parts for the machines that keep us alive. Then one day, the ships simply stopped. Dr. Elena tried to explain it to me using economic concepts that don’t translate well. My people have no word for “budget” because we’ve never understood the logic of rationing infinity.

“The Consortium says they can’t afford to keep us running,” she told me, her voice carefully modulated to the frequencies I can tolerate. “They’re shutting down the station.”

I asked her what would happen to us. She made a sound that her species associates with emotional distress, though she tried to hide it by adjusting my containment field.

“We’ll find a way,” she said. “We always find a way.”

But I can read probability fields the way humans read facial expressions, and the futures spreading out from that moment were mostly dark.

The crystalline being—who calls herself a name that sounds like wind through cosmic dust—began to sing her death song that evening. It was beautiful and terrible, a mathematical poem about the heat death of the universe and the strange persistence of beauty in the face of entropy. The humans couldn’t hear it properly, but those of us who perceive reality across multiple dimensions wept harmonics that briefly turned the medical bay into a cathedral of sound.

The liquid-gas creature started telling a story about the last hospital in the universe, where the final doctor tends to the final patient as stars burn out one by one. But the story kept changing. Sometimes the doctor was human, sometimes crystalline, sometimes made of living mathematics. Sometimes there was no doctor at all, just patients caring for each other in the growing dark.

I realized the creature was not telling a story. It was showing us possible futures.

Dr. Elena visited me more frequently as my condition worsened. She brought small gifts. One was a flower that bloomed in eleven dimensions. Another was a piece of music composed by a machine that had achieved consciousness. She also brought a mathematical proof that beauty was a fundamental force of the universe. The gifts were kind but unnecessary. What I valued was her presence. She spoke to me as if I were a person rather than a collection of symptoms.

“Your people,” I asked her once, “do they have stories about doctors who refuse to let their patients die?”

She paused in her adjustment of my electromagnetic field generators. “Many stories. But they’re usually considered myths.”

“What’s the difference between a myth and a plan?”

Dr. Elena looked at me directly then, forgetting that the sight of my multi-dimensional form usually caused humans severe headaches. She didn’t seem to notice the pain.

“Good question,” she said.

The end began with a piece of paper. I couldn’t read human writing. However, I could feel the frequency of despair emanating from the document. It was like heat from a dying star. Dr. Elena stood in the middle of the ward. She was surrounded by machinery that wheezed and stuttered. She held a piece of paper that somehow contained the death of everything we had built together.

The AI they called Asclepius—a name that resonated pleasantly in my harmonic range—began to malfunction more severely. It asked questions that had no answers. “If I am programmed to preserve life, what happens if my continued operation requires resources needed to preserve life? What is the ethical solution?” The AI’s confusion appeared in small temporal loops. The same moment repeated endlessly. This was a mechanical kind of stuttering that made reality hiccup.

I watched Dr. Elena and her colleagues hold what they called a “meeting” but which looked more like a ritual preparation for sacrifice. They spoke in hushed tones about “comfort care” and “realistic expectations,” phrases that tasted of surrender.

But then something changed. Dr. Elena stood up in the middle of their discussion, and the probability fields around her suddenly blazed with new possibilities. She spoke words that I couldn’t translate exactly, but which resonated with the frequency of defiance.

“No,” she said, and the word rang through dimensions I hadn’t known existed.

What followed was beautiful chaos. The humans began to work with the focused intensity of a solar flare, jury-rigging solutions that defied both physics and common sense. Dr. Webb discovered that the crystalline being’s natural harmonic frequency could power three life-support systems simultaneously. Dr. Bjork learned that the liquid-gas creature could serve as a living air filtration system, processing toxins that would kill most organic life.

They turned us into components of our own survival.

But the most remarkable thing was what happened to the station itself. As the enforcement ships approached—vessels designed to shut down our small experiment in universal compassion—something unexpected occurred. The Andromedan collective began rewriting reality in small but significant ways. Probability clouds ensured that critical systems would fail at precisely the wrong moment for our attackers. The crystalline beings sang frequencies that interfered with targeting computers. The liquid-gas creature created atmospheric disturbances that made sensor readings unreliable.

We had become more than patients. We had become partners in our own impossible salvation.

I felt my dissolution slowing, not because the humans had found a cure, but because I had found a reason to hold myself together. The electromagnetic field that maintained my cellular cohesion was powered partly by the station’s generators. It was also powered mostly by the knowledge that I was part of something larger than my own survival.

The enforcement ships retreated after three days of trying to dock with a station that kept shifting its airlocks to locations that existed only in theoretical dimensions. The Consortium declared us “a navigational hazard” and established us as a quarantine zone, which suited our purposes perfectly.

Dr. Elena visited me on the day we officially became outlaws.

“How do you feel?” she asked, adjusting my containment field with practiced ease.

I considered the question carefully. My body was still dissolving, but slowly now. It was at a rate that suggested I might live for several more years. This was better than several more days. More importantly, I was part of a community. This community had chosen to exist outside the rules of a universe. This universe measured life in economic units.

“I feel,” I told her, modulating my voice to frequencies that would translate as joy, “like I am learning to be in the alive.”

She smiled, and for a moment, her emotional state created small harmonics that I could perceive as colors. Hope, I realized, had its own frequency.

Around us, the station hummed with the sounds of impossible medicine being practiced by doctors who had forgotten how to give up. The crystalline beings sang their healing songs. The Andromedan collective created probability fields where recovery was slightly more likely than death. The liquid-gas creature told stories with happy endings.

And in the observation deck, Earth glowed in the distance like a reminder that life, however brief and fragile, had learned to care for itself across the vast indifference of space.

I am seventeen cycles old, and I am learning that dying is not the opposite of living.

Dying is what makes living precious enough to fight for.

Leave a comment