Tolliver found the bat wedged between cargo containers on C-deck, its wings folded like a broken umbrella. The creature wasn’t dead, not technically. Its tiny chest still rose and fell in shallow spasms, eyes filmed over with something that wasn’t quite mucus.

“Whatcha got there, Toll?” Reece leaned against the bulkhead, sucking on a Syndicate-approved mood stabilizer. The company didn’t care what chemicals you pumped into your system as long as you made quota.

“Some kind of bat,” Tolliver said, crouching. “Never seen one on a cargo run before.”

“Probably snuck in when we loaded at New Singapore.” Reece shrugged. “Toss it out the waste chute.”

But Tolliver didn’t. Something about its struggle resonated with him. Seven months into an eight-month haul from Earth to the mining colonies on Ceres, everyone felt half-dead. Corporate policy: minimal life support, maximal profit.

He took the creature to his quarters, fashioned a makeshift habitat from an empty protein-supplement container. His small act of rebellion against the sterility of space.

Three days later, the bat died. By then, it didn’t matter.

Dr. Elsa Chen noticed it first in the vital readings from the crew’s mandatory neural implants. Subtle anomalies in brain wave patterns—nothing that triggered the med-system’s alert protocols, but enough to make her pull the files for manual review.

“Your thalamus shows unusual activity,” she told Tolliver during his scheduled check-in.

“Is that why I keep hearing music?” he asked, completely earnest. “Old songs, from before the Corporate Wars. My grandfather used to play them.”

Chen frowned. “What music, specifically?”

“You can’t hear it?” Tolliver seemed genuinely surprised. “It’s playing right now.”

She made a note in his file. By the end of the day, three more crew members reported phantom sounds.

Captain Sato stared at the reports scrolling across his retinal display. One-third of the crew now exhibited symptoms: auditory hallucinations, heightened sensory perception, decreased need for sleep. No fever, no conventional signs of viral infection.

“Whatever it is,” Chen said, “it’s rewriting neural pathways. The standard antivirals aren’t touching it.”

“Quarantine?” Sato asked, already knowing the answer.

“Too late. It’s airborne. We’ve all been exposed.”

Sato’s corporate implant throbbed at the base of his skull, urging him to report the situation to headquarters. The implant—standard issue for all captains—ensured compliance with company protocols. But something stopped him. A melody at the edge of his consciousness, familiar yet impossible to place.

“The music,” he said softly. “I can hear it now too.”

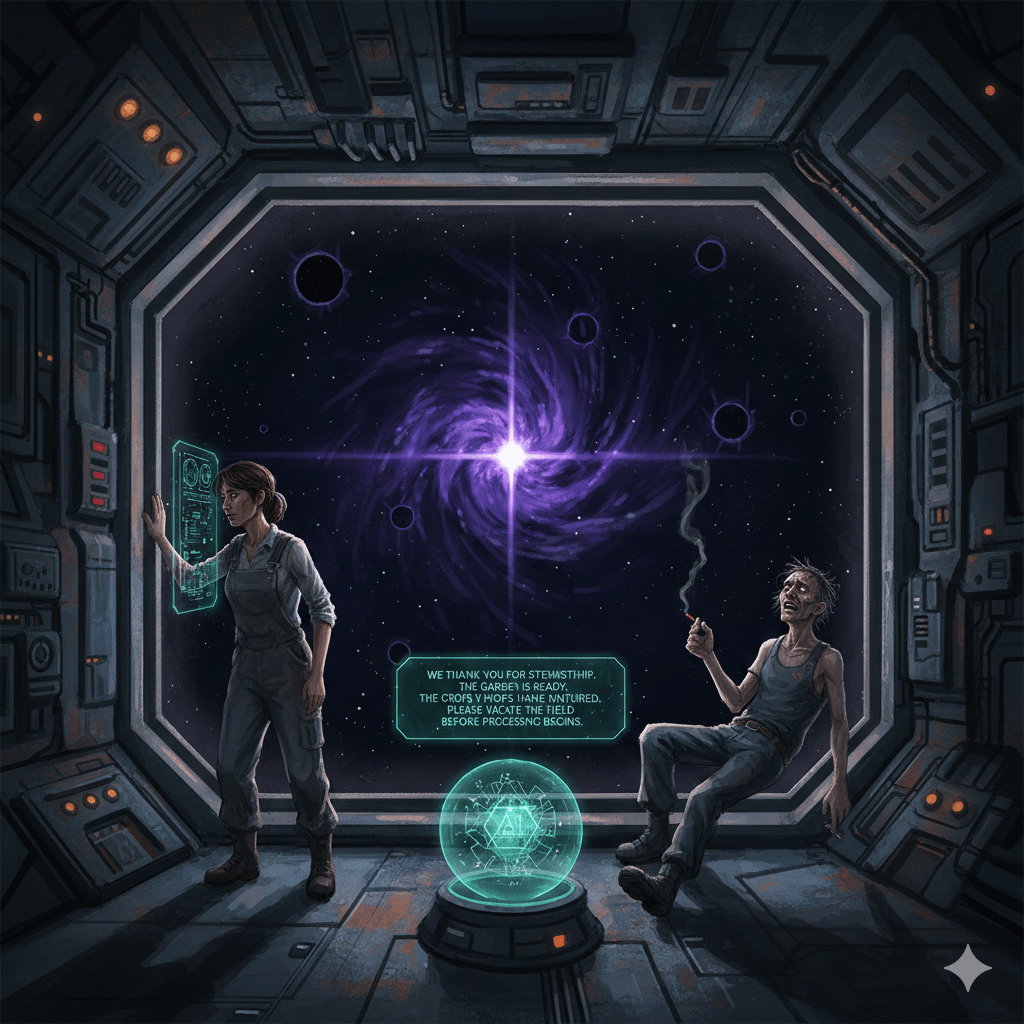

By the time the Iwato Maru reached the Ceres docking station, the entire crew of twenty-seven had transformed. Not physically—at least not in ways obvious to the bioscanners—but fundamentally.

They moved differently, spoke differently. The ship’s security cameras captured them working in perfect synchronization without verbal communication. The recordings showed crew members completing complex tasks while appearing to dance to unheard rhythms.

Keller from Engineering had always been colorblind. Now he painted the engine room in swirls of color he claimed represented the thrumming of the fusion drive. Rivera was the navigation officer who’d never shown creative inclinations. She covered her quarters with intricate fractal patterns. Impossibly, these patterns predicted stellar phenomena the ship’s sensors only detected days later.

They functioned better as a crew than ever before, exceeding efficiency metrics by 43 percent. The corporation might have been pleased, if not for one problem: they no longer responded to direct orders.

The Ceres Quarantine Authority boarded the Iwato Maru in full biohazard gear. They found the crew gathered in the mess hall, sitting in a circle. No one resisted arrest.

During decontamination, Dr. Whitman of the CQA asked Captain Sato what had happened.

“We heard the music of the spheres,” Sato replied, his expression serene. “We remembered what we once were, before corporations carved us into specialized functions.”

“And what’s that?” Whitman asked, checking his handheld for signs of hallucinogens in the air.

“Whole,” said Sato. “Connected. The bat carried a virus older than humanity—dormant in Earth’s caves for millennia. Not a disease. An awakening.”

Whitman made his recommendation: total neural wipe for the crew, sterilization of the ship. Standard protocol for memetic contagions.

But the report never reached his superiors. By morning, Whitman could hear the music too. And beneath his isolation suit, small changes had begun. Neural pathways were reconfiguring. Perceptions were shifting. His consciousness was expanding beyond the narrow confines of corporate personhood.

In his quarters, behind a ventilation grate, a small colony of bats had made their home during the night. Their wings vibrated with the rhythm of human heartbeats, their eyes reflecting a light invisible to unaltered minds.

The change was spreading. And deep in the caves of distant Earth, ancient things stirred, preparing for their return to a world that had forgotten them.

Leave a comment